Jason : Okay. Welcome to another episode of Executive Breakthroughs, I have a

fantastic guest and my speaking coach, founder of Strategic Speaking, Tamsen

Webster. She is going to be talking all about her life, her career and giving you

some inside tips because she is also the woman behind the magic of TEDx

Cambridge, and we are in Boston, so that’s also a nice thing that we’re close by.

Tamsen Webster: It is a nice thing. It is.

Jason : Welcome. Welcome to the show.

Tamsen Webster: Thank you, it’s so nice to see you.

Jason : It’s nice to see you too. I like to give people a taste of where you grew up and a little bit about family and early influences. Why don’t you take us back to that moment when you were that high that was the table or lower, so …

Tamsen Webster: Table or lower. I’m a navy kid, so we moved around quite a bit before I settled in, and I think that had a lasting effect both on me and my sister, actually.

Jason : How so?

Tamsen Webster: Because what’s interesting is that both she and I have ended up in careers where we end up telling stories in a very small amount of time. She is a

screenwriter, she writes in L.A. and she … Most recent project, she was a writer

and a supervising producer on the Handmaid’s Tale on Hulu, and writes for

movies, and etc. I’ve ended up in a career where I help people get big ideas

across in short amounts of time, too. They end up being about the same amount

of time between … movie is, in a lot of ways, equivalent to a keynote or a

workshop, and a TV pilot is about an hour long, and a sitcom is about a half

hour, which gets you to-

Jason : Do you attribute those to anything? To anything that like things that happened?

Tamsen Webster: I do actually, because I think that when you move around a lot, as a kid, you’re in a situation where you have to figure out, “How does this place work? How does this group work? How do I make a mark on this group if I want to? Or how

do I blend in? Or how do I be a part of it?”

I think, whether we realize it or not, it was really good training into very quickly

understanding what were the important moving parts in any place where we

were. Because as kids that moved around a fair amount, she ended up getting

moved a lot more than I did because she was older. You end up being very self-

sufficient. I think that you end up figuring out how to build your own stories, or

how to build your own narrative around how things are working around you. I

think that that has shown up in where each of us have ended up with our

careers.

Jason : You had to do that really quickly, because if you’re moving spot to spot, the

more time it takes you to get adjusted, the less time that you’re actually in the

flow and building relationships with people.

Tamsen Webster: Yes. It can happen early. We stopped moving when I was five, but still, when you move five times before you’re five, there still is this pick up, set down, pick up, set down, pick up, set down that happens. That experience is very different than when we finally settled in, which is Virginia Beach in Virginia … I know I look like a total beach girl. That experience is dramatically different from the vast majority of other people who were in the same schools and all, even

though there were a lot of Navy kids there, because Virginia Beach is a big Navy

town.

Jason : Yes.

Tamsen Webster: It’s still a different background than the majority of people who are born and raised in some place, and so you’re already different coming in. You have to

figure out how different do you want to be? “What’s the nature of my

difference? What’s the nature of this place? What does this group of people

value?” All of those things are pieces of information that I know now, looking

back on it, that I ended up having to pick up.

Jason : That you figured out?

Tamsen Webster: Yeah.

Jason : What made it that you stopped moving? Did your dad get out of the military?

Tamsen Webster: No, my father. No, he was in the Navy for about 21 years,

and my mother also worked as a civilian with the Navy. She worked with the

Navy Family Services Center, so it was basically a social services center for Navy

families because my mother was a PhD in anthropology, which was really

unusual for a woman in the 60s and early 70s to not only have a career, but get

a PhD.

Jason : Yeah, it is.

Tamsen Webster: She was an interesting role model, as well. He decided he didn’t want to be on active duty on ships, and so he ended up taking a desk job in the Navy. Even

then, he ended up being away a lot because the best way for him to do that was

to … for a number of years, was to work up in D.C., so he was in D.C. during the

week and home-

Jason : And on the weekend …

Tamsen Webster: … home on the weekends.

Jason : Even though you weren’t moving, you had a lot of moving parts all the time, in and out.

Tamsen Webster: Yeah, absolutely. A lot of moving parts all the time, but my mother, who was kind of a constant through all. I give my mother a huge amount of credit for all of that.

Jason : How did your mother manage that? I just wonder, I’m just curious.

Tamsen Webster: I still wonder that to this day because she’s … I mean it’s … I’ve got two kids, I don’t know how she did it. I really don’t, and yet sustained a career. She did all of the things that, I think, a lot of people would aspire to now and was doing it in a much more difficult environment then than we have now.

Jason : Definitely.

Tamsen Webster: She’s always been very strong in her convictions. She’s always been an observer, as well, and so as an anthropologist … As a child of an anthropologist, I think, a lot of our observational skills came from her. You don’t really realize what you pick up from your parents, but I can see it with my own kids is that I’m very

much into reading and stories and art and theater and was never very much into

sports and that’s the same with my kids. They do what they see.

Jason : Right, of course.

Tamsen Webster: I think the same thing was true with my mother, we observed her observing. She always is making comments and just noticing things.

Jason : And she was your constant.

Tamsen Webster: And she was our constant, and so I think my sister and I picked up that kind of anthropological observation. It just manifested in different ways based on what our own individual traits were, which is really interesting to see.

Jason : That’s interesting. Did you have any other role … obviously, your mom must

have been some level of role model growing up being in that environment, is

there anyone else who was like a role model or a significant influence?

Tamsen Webster: I think I was one of … It’s commonplace now, but growing up and given all of that, that situation with my dad being there and not, and my mom and all of that. I would say my biggest influence was a group of people that I grew up

with. I had a very close group of friends in middle school and high school that all

oriented around things that we were all interested in. I think, in a lot of ways, it

was a lot of peer mentoring that happened. I see that now with people who are

the age I was then, but it seemed like that was an early wave of it. I see it now

going forward into the careers where there’s a lot of, particularly women my

age, who look and because of the progress that women have made in the

workplace, there aren’t all that many women in a role that is 5, 10, 15, 20 years

ahead of us that provide mentorship back.

I’m part of, at least, three or four different groups of peer mentoring,

masterminds-

Jason : Interesting.

Tamsen Webster: … and coaching circles because that’s what’s there. If you don’t have somebody who’s been on the path before you, then you end up trying to figure out that path together. I think that’s what we did a lot in high school. As it turns out, a lot of the kids that I was friends with also were the children of military of one sort or another.

Jason : It makes sense.

Tamsen Webster: Or their parents were split up, or they had a parent that had a more active role and wasn’t around as much. Even though we had this affinity around the arts, or other things, there’s this other underlying consistency on this mindset that each of us had based on, “Well, we kinda have to figure this out on our own, so let’s

figure it out on our own together.”

Jason : Have to be very self-sufficient along-

Tamsen Webster: Yeah, self-sufficient, independent. I’m not sure how my parents feel about that

now, I think sometimes they regret that they raised two very emotionally

independent kids because we’re-

Jason : I know.

Tamsen Webster: … like the anti-millennials. We love our parents dearly, but neither my sister nor I are the kind that are constantly on the phone and always checking in.

Jason : Call them up, yeah.

Tamsen Webster: My parents are somewhere in the South China Sea right now having a great time, I’m sure.

Jason : See, they’re having good times-

Tamsen Webster: They’re having a great time, yeah. We’re really split up. My sister’s in L.A., I’m in Boston, they’re Pacific Northwest, so I don’t think we could be further apart, but that’s not really because we couldn’t be, it’s just-

J

ason : The way that it worked out.

Tamsen Webster: The way that it worked out.

Jason : What happened in the … you went to school, like-

Tamsen Webster: Yes, I came here to Boston for school and it was funny because at the time-

Jason : Why here?

Tamsen Webster: Why? That’s a good question. It ended up that I came here because a friend of mine thought that all the other places I applied would be absolutely not a good fit with my personality. Having a bit of an independent streak, I decided that I

wanted to go very nontraditional college, and so just about all the college I

applied to other than the … I only applied to Harvard and Amherst, just to see if

I can get in-

Jason : Sure.

Tamsen Webster: … were nontraditional. Evergreen State south of Seattle, Bennington,

Hampshire College out in the Berkshires here in Massachusetts, all places where

you essentially designed your own major, but all of them-

Jason : Interesting.

Tamsen Webster: … were rural. I had a good friend in high school who said, “You are gonna hate that,” even though Virginia Beach wasn’t exactly a city, he was like-

Jason : It’s still a lot different-

Tamsen Webster: It’s a-

Jason : … rural community.

Tamsen Webster: Exactly. He’s like, “You don’t want sheep in your front yard,” and I’m like, “You

know, that’s probably right.” I had gone to a summer program that Harvard runs

for high school students between their junior and senior year. I really loved

Boston and Cambridge and that summer that I was up here. He was like, “Well,

why don’t you just, you know, go to BU? Boston University?” I was like, “Okay,

let me apply there.” They ended up … that was the biggest financial aid package

I got, and it ended up being absolutely the best place, but not because of the

school itself, in a lot of ways. It was because it was the city, that was the best

experience for me here.

Jason : What about the city was …

Tamsen Webster: A number of things. One thing was to give BU credit, I was allowed and able to

essentially design my own major, but within a little bit more structure than I

would have had someplace else.

Jason : Right, [crosstalk 00:11:36]

Tamsen Webster: BU had what’s called a collaborative degree program. Since I had gone … In

Virginia, I had been in essentially a prep school, so had taken a lot of advanced

placement courses, started with a lot of credits. I had a college counselor that

was like, “You know, you’ve got enough credits so you could do a second degree

while you’re here.” I said, “Okay.” I had started in the management school,

studying marketing and market research, and then I added a liberal arts degree

on top of it in American Studies, which very much was a study of culture. I like

to say I don’t know whether it found me or I found it, because it was absolutely

a codifying of how I think about things.

American Studies is an approach to studying culture. It isn’t really about like,

“Go America!” It’s about picking a time period, or picking an idea and looking at

everything around that. I picked the intra war, between World War I and World

War II, and so my role in American Studies was to look at that time period from

every single … From art, from the economy, from politics, to just every … the

culture, political dynamics, I already said politics, but just interactions of

everything.

Jason : It’s kind of anthropological, too.

Tamsen Webster: It is anthropological, yes, absolutely.

Jason : It’s a tongue twister, but it’s like, yes, definitely you’re like mom, you can see

that.

Tamsen Webster: Yeah, I can see that.

Jason : Now-

Tamsen Webster: My look at it was I was kind of bored with just marketing and business, and the

kids that were in the business school weren’t really my people. I was looking for

what would I pair with it? I said, “Well, if I’m gonna be in marketing, then I want

a better understanding of the culture to which I’m going to market.” I wanted

that ability.

Your question was about why the city. As it turns out, because my family was

not wealthy, I needed to work the whole time I was in school, just to have

pocket money and things like that. I ended up working in the night clubs on

Lansdowne Street here in Boston, which is really surprising to people. They’re

like, “What did you do, Tamsen?” As it turns out, I was the box office girl,

because as one of the managers told me, I was the only one they could truly

trust to A, be with the money and B, to count it correctly. I was the one that

took all the money at the door and divided it up and everything … sold tickets

and all of that. I was also the popcorn girl on Sunday nights for movie night, but

the …

What was interesting about that was it allowed me, at a time when I think a lot

of people set their world perspective on what people are like and what their in

groups are and who they want to be, it showed me a much bigger spread of

people than I would have seen in any other way. Actually, before I worked on

Lansdowne Street, I worked in this totally sketch nightclub that was in Kenmore

Square called Narcissus. Anyone who is from Boston would be like, “Oh my God,

you worked at Narcissus?” Yes, because Narcissus was actually where the locals

came. Lansdowne Street was where all the college kids went out at night, but

Narcissus was where the kids who lived on the north, like Revere and all these

places, your classic Boston accent people, they came into town and they worked

at Narcissus.

To see and become friends with those people, and then to get to see a different

group of people at the clubs on Lansdowne Street, it taught me a huge amount

of things, a huge amount. I mean, the first was that a college degree was not

necessary for someone to be a fascinating, fully-formed, interesting human. Yet

that, particularly coming out of a prep school, that’s the narrative that you’re

taught.

Jason : Of course.

Tamsen Webster: Like, “Go, do your work-”

Jason : They have to sell you that.

Tamsen Webster: They have to sell you on that. All of a sudden, I was like, “Well, a lot of the

people that I go to school with, I don’t like but these people that I work with,

many of whom barely, if they got out of high school at all, were amazing people,

really interesting, smart, just well-rounded, real people.” So many of my friends

from college are actually not from college, they’re people I became friends with

while I was in college. Even if they happened to have gone to BU, they weren’t

in my classes, it was because we worked in the clubs together, that’s why, and

it’s crazy, but yeah, little known fact.

Jason : Little known fact.

Tamsen Webster: Little known fact.

Jason : That dovetails with a lot of what you’re talking about in meeting people and the

stories and learning all about all these different people from all walks and

shapes and forms all over the place, and then sort of just being friends with

them outside of the mainstream because that’s now where you had come from,

at all.

Tamsen Webster: Right, right.

Jason : It just makes sense. Now looking back, it looks like okay, that makes real logical

sense that you’d be attracted and want to be doing that outside the norm. You

left school and what happened after that? What was the next-

Tamsen Webster: When I graduated college, was so really in the … This is all in the early 90s, and

this prior to the financial crash of 2008 was like the next most recent really bad

time to be graduating college-

Jason : Yes.

Tamsen Webster: … because it wasn’t good. That was one of the reasons why I went into business,

in the first place, when I was trying to figure out what I wanted to be, because I

was horrified that my sister, who went to Stanford, because eight other people,

and I’m not kidding about that, went to Stanford, I didn’t even apply because

I’m like, “I’m not going to Stanford, everybody else did.” I was just horrified, at

the time, that she went to Stanford for theater. I was like, “You go to Stanford

and you get a theater degree? What the heck are you gonna do with that?” Of

course now, I was like, “Okay, that was smart.”

It was not a good time to get a job and so I … and I love being in school, frankly.

I love learning. I haven’t stopped, obviously. It’s one of the reasons why I love

doing TEDx so much. I feel like I get little intense … Any time I work with a client,

or any speaker, I get an intense education in that particular topic and it’s fun.

I went straight on to grad school and I went to Dallas, actually. I went to

Southern Methodist. I went to SMU because they had a grad school program

that mimicked what I had done as an undergrad. SMU has a program for arts

administration and I wanted to be an art museum director, where you would

get a master’s in arts administration, so essentially a liberal arts master’s degree

and an MBA simultaneously.

It was two years, two summers and I’d get two master’s degrees out of it. I was

like, “All right, it happens to be in Texas, so I’ll go.” I was open to that. There was

a reason why I wanted to go away from home to go to college, I consciously

wanted a different environment for grad school because I felt like I knew the

West Coast because my parents were there, my sister ended up there. I’d been

in the south-ish with Virginia, New England I got and I’m like, “Here’s this giant

part of the country I don’t understand, like let’s-

Jason : Let’s go there.

Tamsen Webster: … let’s go there! And let’s go to Texas!” The food was good. It was awesome.

Texas and I didn’t really get along all that well, because I wasn’t any less

opinionated, or any less brunette in Texas, and particularly in the last 90s when

the economy started picking up again, neither of those things were terribly

popular, particularly in the business community coming out of SMU, at the time.

But it was another one of those things where I’m really glad that I did it, because

always having my feet in kind of two experiences allowed me to have a better

perspective on both. You think about it, there’s-

Jason : It makes sense.

Tamsen Webster: … a reason, we have two eyes, it gives you depth perception. It’s the thing that

allows you to get a better perspective on something. Being able to do that the

whole time allowed me to have that perspective. I ended up getting my MBA at

23, which is super unusual and it’s why I wish that MBA still had continuing

education because I’d love to go back. Once I’ve been out in the world, I’d love

to go back and be like, “Oh, that’s what this was all about.” It was a really

interesting experience because it was … I think we had 114 people in the class,

there were fewer than 20 women in that whole class, I was younger than

everybody else by at least six or seven years. It was, again, an interesting, kind

of fish out of water.

Jason : Mix of people.

Tamsen Webster: Mix of people. The marketing was what I did from undergrad, and so when I

went to SMU, what I really wanted to focus on was, “Well, if that’s external

communication, how does internal communication work?” What I focused on in

undergrad was organizational behavior and organizational structure and

management communications, how you get something to work internally?

Because I was already starting to figure out that a message was never going to

work externally, if it didn’t make internal sense first. That’s where that piece

came in.

I worked both at Banana Republic and got a job at a consulting firm in Dallas

while I was there, the former Pritchett & Associates, now Pritchett, Inc., Price

Pritchett. It’s that typical story of they just threw money at me and I said,

“Okay.” Like, “What art museum?”

Jason : It isn’t a bad thing.

Tamsen Webster: “All right, it’s fine.” After about a year, I was like, “You know, this isn’t what I

wanna do.” I was a change management consultant, that absolutely marked

forever the kind of work that I liked to do, but doing it in Dallas at a consulting

firm wasn’t the right match.

Jason : Wasn’t right.

Tamsen Webster: Yeah.

Jason : Where was next?

Tamsen Webster: Next was, I was like, “Well, to heck with that, I’m gonna go back to the museum

world.” I took a 50% pay cut, moved back to Boston and started to work at a

museum that’s north of here called the Peabody Essex Museum up in Salem,

Massachusetts of witch fame.

Jason : Yes.

Tamsen Webster: Yes. Originally started in what would now be called development

communications, which is the communication strategy behind fundraising. I sat

between essentially the marketing department and the development, the

fundraising department. That evolved into … more of a long story than we

probably have time for. It evolved into my taking over the planning of the

exhibition schedule for the museum.

Jason : Oh, wow.

Tamsen Webster: I put into place their first five-year rolling plan for that, helped manage their

bicentennial exhibition and helped bring it, at that time, the most popular

exhibition they had had to date, which is the story of Ernest Shackleton’s

journey across the Antarctic after his boat got crushed in the ice.

Jason : Oh yeah, I read about that.

Tamsen Webster: That was a fascinating time. That was next. I was there for about three years,

which is my normal tenure. I’m a three year girl.

Jason : Three years, a magical time.

Tamsen Webster: It’s a magical time. My next job was longer than that. It was four and a half

years, I think I had more to do. I learned later that it usually took me about

three years to build a system, and then after the system was built, if I didn’t

have an opportunity to build a new system in that same place, I tended to

move.

The next place I went was still in the arts, but the other, all the rest of them. I

went into … I became the head of marketing and communications for a local

college here called the Boston Conservatory, which is a performing arts college

and they have music, dance and theater. It’s now part of Berklee College of

Music, but at the time, it was still independent.

That was a really interesting … It built on a lot of what I had started to see when

I was at Peabody Essex Museum, which is an institution that wasn’t fully

comfortable being itself. The Peabody Essex Museum really fought against the

fact that it was in Salem. They had all of the papers and all of the artifacts from

the witch trials, but they didn’t want to put them on display because that was

somehow low culture. There’s this vision of we want to be the MFA of the north

shore. I just wanted them to be the Peabody Essex Museum. I thought there

was more strength and more value and more difference there in saying, “Yeah,

we’re actually all of this. We are the quintessential-”

Jason : Instead of trying to fight it off.

Tamsen Webster: Yeah, this quintessentially New England museum, I mean what other museum

could possible extent from everything? From an imported Chinese house, all the

way to-

Jason : That’s actually hurting you, because that’s what you’re known for, why not

leverage that to get more money and funding to do a lot of the other things that

you want to do?

Tamsen Webster: They’ve come to that. I think it was an internal struggle of seeing what worked

and what didn’t over time. When I went to the Boston Conservatory, I started to

see a very similar thing, because Boston is lousy with A, colleges and B, with

conservatories and music schools. There’s a ton of them, not only built into the

universities that are here, but there’s another conservatory. There’s the New

England Conservatory, which is the one that most people actually know.

When I got there, the Boston Conservatory was doing everything it could to look

just like the New England Conservatory. It had a logo that looked like it. The way

it talked about itself was that, and yet the New England Conservatory is just

classical music and the Boston Conservatory was music, dance and musical

theater. There was just this … Any image you might have in your mind about

what dancers and musical theater kids would add to that mix, and you’re

completely right. It was not this staid, formal place.

In fact, when I started talking to the students there to try to get a better handle

on what would be a better way to represent the conservatory, the analogy that

they kept coming back to, and different groups of people would come back, is

they kept describing themselves as the island of misfit toys. This was the only

place that they had ever been where they felt not out of a group, but it was a

whole group of people who are outsiders like that. We just revamped

everything, so that it was much more focused on that energy and that

happened from this cross of all those different disciplines.

Jason : It sounds like they had a little bit of an identity crisis.

Tamsen Webster: Oh, absolutely.

Jason : It seemed like both of the places, a lot of the stuff, it seems like people, they’re

having a crisis about who they are and trying to pull it out, right?

Tamsen Webster: Yeah, and trying to figure out a way to talk about it that makes sense.

Jason : Makes sense to everyone.

Tamsen Webster: Yes. In fact, that the answer is … as I started to discover-

Jason : Which is the same thing you did in school, right? It all really goes back to the

American Studies, right?

Tamsen Webster: Yeah, it’s still what I do now.

Jason : Because it’s looking like you have to look around everything-

Tamsen Webster: And what’s the thing that makes-

Jason : … 360 and what’s the theme and all the different things that are going on, and

be able to pull all that out to really understand what’s going on.

Tamsen Webster: Yeah. If I do one thing, it’s I help people make things make sense. Retroactively,

proactively-

Jason : It makes sense.

Tamsen Webster: … internally, externally just, “What is it that you need to make sense? Okay,

we’re gonna figure that out.”

Jason : It goes back … even going back to mom because I mean that’s-

Tamsen Webster: Going back to mom.

Jason : … what an anthropologist does, right?

Tamsen Webster: That’s right.

Jason : They were able to look at stuff from the outside perspective and bring it all

together, without moving as much bias as possible in the process of doing it.

Tamsen Webster: Yeah, exactly. It’s never been not that, but I didn’t necessarily see it that way, at

the time. At the time, I’m like, “I’m just gonna explain this is … ” Now it’s the rest

of the arts, because there was still this part of me that was like, “Well, I wanted

to be a museum director and I’m not, and so what’s going on there?”

Jason : Did you have a lot of resistance in there?

Tamsen Webster: I didn’t. It was funny because I broke every rule about how you’re supposed to

rebrand an institution. The whole thing you’re supposed to do is you’re

supposed to do the research first and come up with the strategy and come up

with all of that, and then you come up with the logo and all of that stuff.

Because I had no money, I mean my budget was nothing, it was-

Jason : You can’t do that then, and then it’s hard for people to argue with you because

there’s no money to do it.

Tamsen Webster: Absolutely. What I did was I reversed the process. I had a designer that I trusted

very much. I said, “Come up with three radically different directions, based on

my impression so far of what I thought was representative of the feeling

anyway.” Then, I took that to the students, I took it to the faculty, I took it to the

staff and I used that as the basis of the research and said, “Which one of these is

right? Why?”

It all circled in on really one that represented the energy of it, and energy of

everything else. As a product of doing that work, we were also happened to be

working on the organization’s mission statement, at the time, and that was an

enormously collaborative process. One of the things that doing the rebranding

and doing it visually back, rather than strategy forward, helped to crystallize it

much, much faster. It also helped us figure out, as a group, that the thing that

really made the Boston Conservatory different was its focus on working artists.

You might think, “Well, why is that important?” Well, this college costs a lot of

money to send somebody there. If you think about a parent and now we’re into

the first wave of millennials, given the time. This is the time when the

millennials were coming in, the oldest millennials were starting college at the

time I was there. This was also 2001, so there was September 11 happened

while I was there, there was all sorts of stuff.

These were parents that were much closer to their kids, traditionally, than

GenXers like me, or boomers. They’re about to spend a whole bunch of money

to send their kid to art school. Their concern is is this kid going to work?

Jason : Right.

Tamsen Webster: The kids are just … they have a dream and they’ve got enormous talent and

whatever, but the parents are like, “Are you going to work?”

Jason : “Are you going to have a job? [crosstalk 00:30:42] survive?”

Tamsen Webster: Yeah, exactly.

Jason : Especially if they’re going through the downturn.

Tamsen Webster: Right. What we really focused on was not that we were subsuming quality,

because my feeling was any time a college comes out with like, “We’ve got

diversity and we’re student-centered and we’ve got excellent faculty.” That’s

table stakes. You can’t distinguish based on that-

Jason : Everyone knows that.

Tamsen Webster: Everyone. If you don’t, what the heck are you doing in business?

Jason : Yeah.

Tamsen Webster: It wasn’t that the quality of the education wasn’t important, it was just we were

looking at it through the lens of how can you work, if the quality isn’t great?

How can you work, if you don’t replicate working conditions?

That’s where the presence of all three disciplines there was really helpful,

because students who came to be classical musicians were playing in the pit

orchestras of the dance and the musical theater productions-

Jason : Got it.

Tamsen Webster: … which is, by the way, where the vast majority of classical musicians end up

working is in pits of shows, not at the Boston Symphony Orchestra, or

something like that. It ended up being a really powerful way to not only attract

the right students to the organization, but eventually a really powerful basis for

fundraising. You could say … Let me be clear, the conditions were not great. In

fact, when I first started there, they had a picture of some other institution’s

theater on the front of the materials that were sent to the students.

Jason : That’s funny.

Tamsen Webster: They were so … We don’t show it. It became the basis of a very successful

fundraising that happened that really saw its peak after I left, where they could

say, “If we can get this kind of quality with these conditions, imagine what we

could do if they were good.”

Now, they’ve become so successful, they’ve built two … they renovated a

building, they built another one, the acquired and renovated a third. Then, the

successful, so far, merger with Berklee. That’s been cool to see. I can’t take any

credit for that piece, but it was fun to see it at the beginning.

Jason : It could be a part of the evolution of everything that’s going on.

Tamsen Webster: Yeah.

Jason : You left there, that was a little bit longer and …

Tamsen Webster: It was, because it was meatier. The shift was, once we had the brand in place, it

started to be how now do we swing the strategy of the school? I got to be

involved a little bit more in that. How do we set the curriculum up differently, so

that we can achieve this aspiration we have of a truly interdisciplinary-

Jason : That’s a pretty complex problem, too.

Tamsen Webster: Yeah. Then, from a career standpoint, I was looking at and saying, “Well, what

am I ready to do?” I still loved the consultant aspect way back from Pritchett in

Dallas. I was like, “Well, do I want to be a consultant? Or do I want to go forward

in … still towards the path of nonprofit administration?”

Given the fact that my background was always in marketing, you don’t get very

far in nonprofits, unless you know how to raise money. Even though I helped

with both admissions communication strategy and fundraising communication

strategy at the Conservatory, it wasn’t my main job. I was like, “Well, I wanna

see how a great fundraising operation works and I want to cut my teeth on

that.”

The next place I ended up was at Harvard Medical School, at which point I

couldn’t claim any arts at all, but it was really a very calculated decision to figure

out how does this other piece of this work? I went to Harvard Medical School

and was in charge of the fundraising communication strategy. My job was to

figure out how to help the gift officers, the people who had to go ask people for

money, how to ask people for money for Harvard? Which, if you stop and think

about it, is not that easy of a job, because [we’re 00:34:31] Harvard a country,

its GDP … its endowment would be a GDP equal to like the 18th largest country

in the world. They’ve got money. Needing money really couldn’t have been the

message, so it was a fun puzzle to have to figure out of, “Well, how do we make

that case? Why would people give money?”

Jason : How can we make a compelling case for people to give us money, when we

can’t use the fact that we, you know-

Tamsen Webster: We can’t use the fact that, “Help us … ”

Jason : Help us.

Tamsen Webster: Like, “Help us keep the lights on,” which was part of the message for the

Conservatory, which was-

Jason : Which is most of the time for nonprofits.

Tamsen Webster: Right. It was a fascinating thing to see, and it got me into the scientific world,

because there’s this extra layer of difficulty, an extra layer of difficulty for the

medical school because, unlike every other medical school in the world, Harvard

doesn’t have its own hospital. It has 17 of them. There’s a bunch of hospitals

here in Boston, Brigham and Women’s, Mass General, all sorts of … that are all

teaching hospitals for Harvard, but it’s not like Johns Hopkins University has

Johns Hopkins Medical Center, which means that as Harvard Medical School we

couldn’t fundraise from the patients of those hospitals because they had their

own fundraising arm.

Jason : Got it.

Tamsen Webster: The people that we could talk to were people who were interested in science, in

medicine in Boston, but probably weren’t scientists, or clinicians, or doctors

themselves.

Jason : Interesting.

Tamsen Webster: The other thing we had to do-

Tamsen Webster: … is how to explain what the actual work of the medical school was? It’s

something that … it’s called basic science, which is not basic at all. The way I

would ended up describing it to most people was that fundamental science, we

were really interested in what are the fundamental questions of why do people

get sick? Why are they healthy? Why don’t we know the answers to these

questions yet?

It was really my first … the first time I started to codify, in any real way, that

there was certain fundamental questions that people needed to have answered

about something before they would act on it. I loved working there, because it

was … One of the projects that I did right almost off the bat, because we were

trying to develop all these new materials, was I interviewed close to a quarter of

the entire faculty of the medical school. Just to be able to talk to these world

class-

Jason : Yeah, that’s pretty amazing how much you can learn and …

Tamsen Webster: … academics, researchers, scientists about just everything from neuroscience,

to systems biology, to macro biology, to infectious diseases, to just all of this, all

of it, and just seeing what were the frustrations? And why were they doing it?

What were they passionate about? Trying to figure out how to take all of that

and weave a narrative together that would make it easy for someone to go and

have a chat with some business person who has no background in science, or

medicine and be able to really powerfully and effectively explain why investing

in a medical school was the path to that individual donor achieving their own

personal goals.

Jason : Got it.

Tamsen Webster: That was fun, flat out fun, it was great, I loved that.

Jason : The ride had to end?

Tamsen Webster: It did have to end because … personnel changes. It was a time of enormous

upheaval at Harvard, as well. In the time that I was there, there were three

presidents … I had three different presidents of Harvard, three different deans

of the medical school-

Jason : Wow.

Tamsen Webster: … and then three different bosses in my office over three years. Everything was

changing at every level, and eventually just got to a point, I was just like, “I need

something that doesn’t change, for just a little while.” That was also the time

where I had my first son and I was like, “Okay, there’s-

Jason : Too much.

Tamsen Webster: … there’s too much, I just need things to stop for a little while.”

Jason : You were at your three years, too.

Tamsen Webster: I was at my three years, and I had built that system thanks to the change, it

didn’t survive much after leaving, but those contacts are still really powerful.

Jason : That’s good.

Tamsen Webster: Other people in the … I still do work for people that I worked with there.

Jason : Okay.

Tamsen Webster: With TEDx, it’s interesting how much in two ways it comes back. A, a lot of the

sponsors and organizational partners for TEDx Cambridge are some of those

people we were asking money of 15, 20 years ago now, or 15 years ago now.

Second, my ability to speak science has come in very handy. That summer I

spent talking to scientists and understanding what they do, whenever I meet a

scientist now, it doesn’t take very long before they’re like, “What did you

study?” Because they’re trying to figure out how I understand-

Jason : How do you figure it all out.

Tamsen Webster: How do I understand what it is because-

Jason : What they’re doing.

Tamsen Webster: … they’re only used to other scientists being able to understand it. I’d like to say

now that I forgot to study science because I do, I adore science. I was coming

out of high school, as I said, I was worried about getting a job and being an art

museum director, and so science didn’t play a part. I’m glad it came back later.

Jason : What was next? What was …

Tamsen Webster: After that, I decided that now was the time that I wanted to head back into

consulting a bit. I wasn’t ready, at that time, to be an entrepreneur. I

contemplated it, but I’m glad I didn’t then. I went to work for a company that I

had hired while I was at the medical school that … We worked together to put

all the materials together, the ones that didn’t end up really getting used.

They’re a local brand strategy firm here in Boston called Sametz Blackstone,

they still do wonderful work. They tend to focus on cultural institutions, higher

education, companies and organizations with a mission, with a purpose, even

when they’re working for corporations, their best fit is for corporations that do

more.

I wore a lot of hats there. I was part brand strategist, based on the fact that I

had been, at that point, 15 years as a brand marketer. I was also business

development, to some extent, and this is now the late 2000s, so this is when

social started to pop up. I ended up being their first digital and content

strategist. Then, because I was one of the only people who had managed people

when there was a shift in responsibility for their IT group, I ended up taking over

and managing their web development team, as well.

I did that for three years, wearing those multiple hats, and really helping them

move their brand strategy thinking … I’d like to think I helped them move their

brand strategy thinking into what does it look like dispersed digitally? It helped

me understand what is it that an organization buys when they buy brand

strategy? Where does that work? Where does it break? Sametz does a

wonderful work with positioning, and they do great work in graphic identity,

and getting something that really captures an organization and what it’s for.

I could see how organizations would really struggle because they would ask us,

they were like, “What do we say day to day?” That wasn’t Sametz’s role, they

were always very clear on it, but there was a gap with what do you do day-to-

day with that? It can be a wonderful brand, a wonderful strategy, but what do

you do day-to-day?

Jason : Day-to-day, yeah.

Tamsen Webster: That became the next question I wanted to answer. “How do I make that make

sense? How do I make a big high level brand make sense day-to-day?”

Jason : Day-to-day.

Tamsen Webster: That was a place where having gotten in early in social ended up working out for

me very well because I was connected with other people here in town that were

also doing similar things. A friend of mine who was heading up the kind of an

experimental digital marketing division of a local advertising agency, a place

called Allen & Gerritsen said, “Hey, do you want to come be part of that? I need

somebody who understands … ” He saw me as someone who really understood

how influence networks worked because he’d seen me do it, he’d seen me

figure out who were the people-

Jason : And you’d been doing this in all these different ways.

Tamsen Webster: In all these different ways, I’d been figuring out how to do it, so he wanted me

to come in and do that. Over the course of three years-

Jason : Of course.

Tamsen Webster: … I ended up taking over that group and expanding it to a broader community

management, content, digital, social, and really figuring out, “Well, were was

the break in … ” Okay, now I could figure out this is what we need to be able to

produce day-to-day and how important it was to have a high level strategy that

made sense.

I could also start to see the seeds that there was still something missing in

between, which is there was this gap between day-to-day content and high level

brand, which turned out to be messaging, which was a big hole in offerings in

the marketplace in general.

Jason : Yes.

Tamsen Webster: We started to build that out a little bit. Then, as it often happens in

organizations, there was a change in-

Jason : Leadership.

Tamsen Webster: Yes, not so much at the highest level. In this case, what happened was the

agency acquired another agency and that changed all the internal-

Jason : Dynamics.

Tamsen Webster: … dynamics and things that were … Because they wanted to become a bigger

agency, it meant that the boxes around positions got more sharply drawn. I was

at a point in my career where I didn’t want that sharp of a box around me. I had

seen the sparkle of the next step because I had … there was a group that had

come in to do training for us, while I was at Allen & Gerritsen, on how to

develop messages for sales presentations or for pitches, which people in

advertising have to do all the time. I was very involved in almost all … I’d say a

significant proportion, a majority of the new business pitches because, at that

time, everybody wanted social to be tacked onto their creative strategy, and so

that was usually where it was. Because I had spent so much time presenting on

behalf of the organizations I had worked with before and always focusing on

communications, I ended up being, a lot of times, the very last presenter, and so

the person that was in the position of wrapping up the pitch.

When this company came in, it was a company called Oratium. It was a two-day

workshop. After the first day, I was like … I went up to the CEO of the company

and I said, “This is my dream job, how do I get it?” Six months later, I was

working for them, because I was like, “Now I wanna figure this piece out. How

do I figure out messaging? How do I do that?” That’s where I ended up next was

Oratium, which is a boutique messaging consultancy, is probably the best way

to describe it.

The Oratium training and consulting firm, I think, the training was very much

where most of the money and the profit and the revenue came in. Training,

again, around presentation skills that weren’t really about presentation skills, it

was much more about understanding how the brain works. The CEO was a big

fan of neuroscience, and so this is where I got my science thing fix back in, and

was a big fan of how do you match messaging to how people’s brains work?

Tamsen Webster: It was super interesting-

Jason : This started the entrepreneurial itch.

Tamsen Webster: It did. It did, because they were gracious enough, while I was there, to allow me

to be entrepreneurial while I was there, in certain ways. At this point, I had

learned enough about my career that I really like working individually with

people, and yet this was a company that [inaudible 00:46:49] training to large

groups of people. I had cut my teeth on training per se, and Weight Watchers,

which I know we haven’t even gotten to yet. I was very comfortable in that

environment, but I really loved just being able to sit down and figure out like,

“How do we do this thing?”

Jason : You also weren’t, at this point, sort of getting the big picture, getting in the

middle, and then you got yourself into a box, at this point, that there really …

there wasn’t anywhere else you could go other than on your own.

Tamsen Webster: Yes, because there wasn’t really anybody doing the things that I wanted to be

doing. While I was at Oratium, one of the normal and natural evolutions out of

training was that we would train people on how to build a better sales message,

and then they would want to do that. Or we would train them on a better way

to put a high stakes talk together, like a sales kickoff speech from the CEO. Then,

they would want help building that. I ended up being the one that helped do

most of that coaching, particularly the one-on-one with executive, because at

the same time I started at Oratium, was the same time I started at TEDx

Cambridge as the executive producer, where I was coaching those speakers on

how to put those talks together. I developed a coaching methodology with TEDx

Cambridge, which then I mapped over to our clients at Oratium, which I was-

Jason : It came full circle.

Tamsen Webster: … between the two of them, I was able to-

Jason : You basically were testing out your business before in a startup inside of the

business that you already had-

Tamsen Webster: Yeah, very much.

Jason : … and then you knew that you had something enough to go out and to do it.

Tamsen Webster: Yeah, and it was a very amicable separation because it’s … coaching and

consulting on that level is not a scalable model for a business.

Jason : It’s not.

Tamsen Webster: No. I’m clear on that, as an entrepreneur. That’s been clear for me from the get-

go, I’m not trying to scale me, like if you hire me, you’re hiring me and I want to

set it up so that you get me and you feel like you’re getting me.

Jason : Yes.

Tamsen Webster: That made sense. I was like, “I really want to focus on coaching,” and I’m like, “I

get that doesn’t make you guys money.” They said, “Well, great, godspeed.” I

still, if you want to do larger scale training on great understanding of the better

way to build messages more broadly, or a sales pitch, Oratium is where you

should go. It’s great stuff, great stuff.

Jason : Before we get into what you’re doing now, get into the Weight Watchers story

because I think that’s pretty …

Tamsen Webster: It was like, “Pkoo!”

Jason : That’s pretty important story, so …

Tamsen Webster: It is a pretty important story so … which feeds into some of the Dallas stuff,

because it was in Dallas where I reached my highest weight. That’s all kind of

tied into it. When I came back from Dallas, I weighed-

Jason : It made you very self-conscious being in that environment?

Tamsen Webster: Oh my gosh, yeah, you just add to that. A, outspoken, B, brunette. I know I’m

making a bigger deal about the brunette thing, but I mean there were literally

times where I went into get my hair done and people were like, “Don’t you want

it to be blond?” I’m like, “Oh my god, no, I would look terrible with blond hair.”

Like, “Is it really that important for it to be blond?” New Englander, outspoken,

brunette, and add to that overweight, which was not friendly in the bubble that

is the villages of Southern-

Jason : No.

Tamsen Webster: … Methodist. You are expected to be-

Jason : And the warmer the climate, the more that it’s-

Tamsen Webster: Yes. The more smaller they expect you to be, right. Yeah.

Jason : The more people see you because you can’t … I mean you have to wear less

clothes because that’s all you can do.

Tamsen Webster: Yes, because it’s hot, yes-

Jason : It’s hot.

Tamsen Webster: Exactly. It was … My working there, so I didn’t notice it really while I was in

school. What started it all was my mother had come to help set up my new

apartment right before I started at Pritchett. The night before I was going to go

for my first day, I was just like, “Well, let me just test out the suit that I’m

planning on wearing,” and it literally didn’t close. I was just like, “What?”

Because I had spent the whole summer in stuff that was loose and form-fitting

because I had spent the summer back up in Boston, and not in Dallas, and stuff

was loose and form-fitting, I hadn’t worn anything tailored, and I literally could

not close the suit that I was supposed to wear the next day, so my mother-

Jason : How did that make you feel in that moment when that happened? Like what-

Tamsen Webster: I was just floored. I really was just so baffled by it. I can look back now and be

like, “Well, Tam, when you’re eating pizza and beer the whole time, what do you

expect?” I was so floored. It was panic because I was like, “What the hell am I

gonna do? How do I feel strong in this new place when something that I’ve

always felt very secure about suddenly … like how I look and how I dress and

always feeling put together … ” I always felt put together. I won’t say that I ever

felt anything more than that, but I always felt like, “I’m put together.” That, all

of a sudden, that was just like, “Whoosh!”

Jason : That was story was just completely crushed.

Tamsen Webster: Yeah, absolutely. I would tell this story later in my Weight Watcher meetings,

but my mom, she was like, “Alright, we’ll figure this out!” The only suit that did

fit, like didn’t have buttons on it, it was like one of those things I had bought and

just hadn’t gotten it. She was like, “Alright, we’re going!” She bundled me in her

car, we go to the only place that’s open at that time of night, which was

Walmart and Walmart, at least at that time, still had a sewing section. We

picked up buttons and we picked up a scale, which I stood on and cried because

it was like oh my god, I had never seen that number associated with me and …

We got it all put together and, in my mother’s inimitable way, it was like, “Oh,

we’re just gonna figure it out and we’ll figure it out.”

It started there, but even then, I had mentally changed my perspective of myself

that I was the average American woman because at the height that I am, 5’4,

which is the average American woman, that the weight that I had gotten to was

also the average American woman but the average American woman is

overweight. It had so sunk into my psyche that that’s what I was that it didn’t

even occur to me that I could be any different, even though all through high

school and college I was small. I actually weigh the same now as I did in high

school, college was more and then it just kind of kept going. It just didn’t occur

to me.

Then, I remember meeting … there was this woman, I believe her name was

Janet, or Janice at Pritchett, and she was just talking to me and some of my

girlfriends at work one day, and she was like, “Yeah, I used to be overweight.”

She’s like, “I used to weigh X,” and she named the number that I was. She’s like,

“And I’m only 5’4,” and I’m like, “That’s how tall I am.” Yet, this was this tiny

woman and I was just like, “Wait, what?” Like, “Hey, huh?”

It was really interesting, because she had lost her weight through Jazzercize,

such an early 90s thing, it’s awesome. I went to a Jazzercize thing and I’m like,

“Okay, Jazzercize is not for me.”

Jason : No, no.

Tamsen Webster: It was enough to set this little spark in my mind that there was something …

that it was possible. I’m like, “Wait, she did it.” I would never have guessed that

she was overweight. She was describing how she felt before she lost weight to a

T, she was sleepy and it would … and all this stuff.

Then, she was this super energetic, like beautiful, tiny woman and I was like,

“Huh!” It took me a couple of years before I was like, “Alright, I’m done,” and I

was back in Boston and homesick one day, and that was another thing that just

got me annoyed. I was sick all the time. I was watching Oprah, homesick. Oprah

had on Sarah Ferguson, the Duchess of York, who at the time, was Weight

Watchers

Jason : Watchers, yeah,

Tamsen Webster: … spokesperson. This was this hysterical back and forth between the two of

them, supposedly trying to make chocolate chip cookies, when neither of them

clearly does any cooking for themselves at all. It was very funny, from that

perspective. I also remember Fergie talking about how she could still have wine

on Weight Watchers. I was like, “Well, alrighty then, I want to figure this out.”

That, plus the fact that my mother-in-law, at the time, had successfully lost

weight on Weight Watchers. The next Saturday, I went in and signed up. Over

the course of … From a total high point in Dallas, to where I am now, it was a

total of 50, 52 pounds, which I’ve sustained now since 1999 across two kids. I

gained weight with both of my kids, and lost both of that, so … which it’s funny,

because when I talk to anybody about that, but particularly doctors, they’re like,

“You know that that’s really unusual, right?”

Jason : To sustain it.

Tamsen Webster: To sustain it, yeah.

Jason : Not to have the up and down, what do you attribute that to?

Tamsen Webster: I think in the beginning, it was being a Weight Watchers leader, because I was

someone who was really … It’s had its dark moments for me as well, but it’s

really so tied into A, people’s expectations of me, but ultimately the way I’ve

grown into that is that it was really important for to be … the word I like to use

is consonant. It’s the opposite of dissonant. Congruence is another word you

could use for it, but it was really important for me to be consonant. I became a

Weight Watchers leader. I started working for Weight Watchers first as a

receptionist, which is what they call the people who weigh people. For a year

and a half I just did that, because I didn’t feel like I was the right person to be up

in front of the room.

That was great training, as well, because the person at the scale is the person

who has to deal in the moment with somebody’s reaction. That’s the person

who has absolutely one-on-one interaction with everybody that comes in. You

end up being the person that learns where people struggle, that starts to figure

out what are the concepts that people are getting and they’re not getting. What

are the things that I can tell people really quickly that it’s going to help turn it

around? I had enough people, both receptionists, fellow receptionists and

members alike, who were like, “Why aren’t you a leader?” I was just like, “I

don’t know.” I decided to get the training for to become a leader, and then

never really looked back, but I always maintained being a receptionist too.

I, at the high point … and I was always doing this in addition to my full-time job.

At the high point, there was about a five to seven-year stretch of the 13 years I

was the leader, where it was five meetings a week that I would lead, two on

Sunday, there was Wednesday night, Thursday morning, Saturday and then I

would also … was a receptionist at least one night a week, as well.

I think part of what helped me maintain, at the beginning, was that there was

no way I was going to get up in front of people and not do what I was asking

them to do. It was a form of self-accountability. It became so effective that, in

fact, eventually that was exactly the same reason why I stopped being a Weight

Watchers leader because it had become so second nature that I was no longer

able to really put myself in the moment where they were. I didn’t think that was

fair.

Jason : Yeah, because you had just … Like anything else, and to be honest, your whole

life had been three years and out so this is not …

Tamsen Webster: So 13! My longest running job was Weight Watchers and it was 15 years. For me

to have done anything for that long was …

Jason : That’s where, but when you … Three is a number that ran its course. I think it

ran its course when you were doing it because you thought it was just habit and

second nature anymore, and it’s like you going through. I think the important

thing is to know when the end is and then go on to the next thing.

Tamsen Webster: Yeah. That happened … It was another one of those things where a bunch of

things happened at the same time that made it clear that it was the right time. I

got divorced right around that time. Weight Watchers changed its program

again. The thing is that any time Weight Watchers changes its program, the

program is wonderful as it is. The programs are really geared towards losing

weight and not so much maintaining it. Because I had always been so successful

on Weight Watchers, I had nothing to lose. I couldn’t experience the new

program as somebody losing weight. I could only experience it as somebody

maintaining it. I just got to a point where I was just like I can’t-

Jason : It’s time to go.

Tamsen Webster: … I can’t make that up. I will not be anything but truthful and I don’t want to

represent that I’m still struggling with it when I’m not. I get that I can stand up

there and be a role model for people, but I know for me, it felt like I was most

effective when I could be right there in the trenches with them and go, “I get it.”

Jason : Of course, emotionally and when you can’t bridge the gap.

Tamsen Webster: Yep.

Jason : Let’s go where you are right now, doing a lot of great stuff, and we’ll put stuff in

the show notes about speaking and how can people reach out to you. What

advice would you have for someone who wants to create a great speech?

Because people always say, “I want to go create something great and fast track

it and not take the slow boat of doing it.” What are a few things that you would

tell someone to start doing in order to get down that road?

Tamsen Webster: It builds on that idea of consonance that I was saying. The best speeches and

the best messages, because really that’s ultimately … a speech is just a

crystallization of a message, come from that congruence, that consonance

between a couple of different things.

One is, and the most important piece is, is it consonant with you and who you

are? One of the biggest mistakes, or one of the biggest missteps, I think, I see a

lot of people do when they’re putting a speech together, particularly if they’ve

got like TEDx, or something on the bucket list, is they go looking for an idea that

they think will be popular, rather than one that is what they’ve been doing the

whole time.

Jason : Or internally motivated.

Tamsen Webster: Yeah. You can look at it as coming from either direction, but if you think even

though everything we’ve talked about today, always the strongest basis of

change is where you are right now. If you’re not happy with where you are, then

you can’t make that leap. The biggest leaps start on stable ground. That’s a thing

I learned at Weight Watchers. The people who would walk in, you could come

up with as many different things and rules of thumb for who would be

successful and who would not, but the only one that was consistent over time,

the only one that was consistent over time was somebody who was happy with

who they were, as a person, and they just felt like the outside didn’t match.

They weren’t waiting to be a better person when they lost weight, they were

already happy with where they were, as a person. That same thing is true-

Jason : They felt enough sort of ala BrenŽ Brown today, right?

Tamsen Webster: Yeah. That this is stable, that say, “You know what? I get that … ” The way I

always described it when people said, “Well, why did you lose weight?” I said, “I

lost weight because I wanted to reduce the traffic noise in my head.” Yes, there

was some vanity there, but I just wanted … There were too many other cool

things for me to focus on, rather than how much my hips were shaking when I

was walking down a street. That was distracting for me, and I’m like, “It’s

distracting me from things that I care about more, so I want that to go away

because I wanna be able to focus on the things I wanna be able to focus on.”

The people that I would see be successful from Weight Watchers, the brands I

would see, the companies I’d see that were most successful are the ones that

manage to capture and build on what they were already manifesting. What they

already were, rather than, “Here’s the thing I wanna be, what do I need to do to

build there?”

When you focus only on where you want to go, you’re focusing on that end goal

and the bridge and you’re completely ignoring that it’s not anchored to

anything. When it comes to a great speech, everybody is already living a really

powerful message, your job is to figure out what that message is. Not to go

manufacture it, to reveal the one that you’re already living.

Jason : Because if not, you’re going to keep struggling with it all the time.

Tamsen Webster: Always, you’re always. And-

Jason : Or you’re going to come up with a good speech, but not a great speech.

Tamsen Webster: Right. Can you make money on it? Can you have a good speaking career? Can

people invite you to speak with it? Yes, but I’ve discovered in this year that I’ve

been an entrepreneur and doing this work that I’m for people who want more

than that. I want people who really say, “I really wanna be great and I’m willing

to do that work. I’m willing to do the research, I’m willing to do that digging. I’m

willing to do that work to really figure out what that is. And I’m willing for that

to be surprised by what that is.”

I see that with my corporate clients, because I do the same process that I do for

speeches with companies as a pre-branding exercise. One of the things I learned

from being a brand strategist is it doesn’t matter how much money you spend

on a brand strategy, if you don’t actually understand what your company’s all

about first.

What I discovered is we can do the same thing. The same thing can help us get

to the core of an idea for a person, I can do in the same amount of a half day to

a day for a company and come to the same kind of clarity. If you start there,

everything is stronger. That’s the first thing, is that consonance with the

message, or the red thread, as I call it, that you’re already using.

Then, the other consonance that’s important from a speech standpoint is it

needs to be constant with what your goals are. What I mean by that is, if you

want to be a keynote speaker at conferences, but your message is a thing that

you totally love is like down and dirty workshops, then those are two things that

are not on the surface necessarily going to line up. That means you need to be

really clear about not that that’s not possible, but that’s, again, going to take

more thought and more work in order to make those things work with each

other, either. It means that you’re going to have a different … Are we over our

time? That’s possible.

Tamsen Webster: Where’s the best place to start? The other thing that we have to be consonant

about is between what that message is and what your goals are, because if your

goals are to be a keynote, like conference speaker, but the message that you

have is a really tactical, down and dirty how to, then that means that it’s not

that that goal is impossible, but it means that you’re going to have to be willing

to do some different things in order to get those two things to line up.

Now, different things. One of them can be well, why do you want to be a

keynote speaker? Is it an income thing because you could probably make just as

much money as a really effective trainer and get to it that way. Or you can say,

“Are you willing to bust the model of keynote speaking and make it much more

experiential?” That’s a way to do it, too. It may mean that you’re harder to

market, it may mean that it’s going to be slower for you to get to where you’re

going but, again, are you willing to do that?

Then the third thing that I think that needs to be consonant for a great speech is

that you need to be consonant with what the audience needs in the moment.

This is a place where I differ from some people, because there’s some people

who say, “Well, you should be … If you are a jeans wearing, cowboy boot

wearing person all the time, then never change it.” I’m of the mind and of the

opinion that the message is more important than anything else. If that means

for a particular audience, it makes more sense for you to shift a little bit. I’m not

saying to divest of your normal personal style, but shift a little bit. You can still

wear the cowboy boots. Can you wear them with a suit instead? Like you are,

Jason.

Jason : Yeah.

Tamsen Webster: Can you shift that, or your style because if you’re super, super casual but you’re

speaking to investment bankers, I think your message is going to be heard

better-

Jason : It’s going to detract.

Tamsen Webster: It’s going to detract, and so being able to be fluid in that way, I think, is where

the most power comes.

Jason : That’s fantastic. Thank you-

Tamsen Webster: You’re welcome.

Jason : … for being on another episode of Executive Breakthroughs. She’s a fantastic

speaking coach, [inaudible 01:09:11] give that out.

Tamsen Webster: Thank you.

Jason : Then we’ll give all the information, a lot of other tidbits in the show notes, so

you’ll be able to take your speech, whether you’re on a corporation, or an

individual, up to the highest level. Thank you, again, for being on the show.

Tamsen Webster: You’re welcome, thanks for having me.

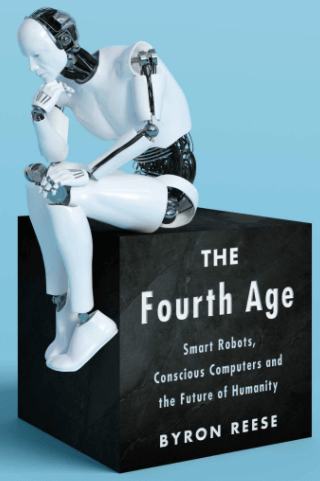

Byron Reese (@byronreese) is an investor, entrepreneur, publisher and futurist. He is the publisher of tech news site Gigaom and the founder of several high-tech companies. He has obtained or has pending patents in disciplines as varied as crowdsourcing, content creation, and psychographics. He is the author of the best selling book, Infinite Progress: How Technology and the Internet Will End Ignorance, Disease, Hunger, Poverty, and War. He currently serves as Chief Executive Officer for Knowingly, a venture-backed Internet startup based in Austin, Texas.He also has a TEDxAustin talk on “Achieving Greatness is a Choice.”

Byron Reese (@byronreese) is an investor, entrepreneur, publisher and futurist. He is the publisher of tech news site Gigaom and the founder of several high-tech companies. He has obtained or has pending patents in disciplines as varied as crowdsourcing, content creation, and psychographics. He is the author of the best selling book, Infinite Progress: How Technology and the Internet Will End Ignorance, Disease, Hunger, Poverty, and War. He currently serves as Chief Executive Officer for Knowingly, a venture-backed Internet startup based in Austin, Texas.He also has a TEDxAustin talk on “Achieving Greatness is a Choice.” The Fourth Age is his upcoming book. Byron Reese explains that a number of disruptive technologies—each of which alone would be world-changing—are all converging at the same time in a perfect storm. We are building robots that can do human jobs. We are designing computers that might be capable of intelligence. We are likely on the cusp of creating a new life form: a conscious computer to which we could outsource our thinking minds, with a companion robot to perform the functions of our bodies.

The Fourth Age is his upcoming book. Byron Reese explains that a number of disruptive technologies—each of which alone would be world-changing—are all converging at the same time in a perfect storm. We are building robots that can do human jobs. We are designing computers that might be capable of intelligence. We are likely on the cusp of creating a new life form: a conscious computer to which we could outsource our thinking minds, with a companion robot to perform the functions of our bodies.

Jason Treu is an executive coach. He has "in the trenches experience" helping build a billion dollar company and working with many Fortune 100 companies. He's worked alongside well-known CEOs such as Steve Jobs, Mark Hurd (at HP), Mark Cuban, and many others. Through his coaching, his clients have met industry titans such as Tim Cook, Bill Gates, Richard Branson, Peter Diamandis, Chris Anderson, and many others. He's also helped his clients create more than $1 billion dollars in wealth over the past three years and secure seats on influential boards such as TED and xPrize. His bestselling book, Social Wealth, the how-to-guide on building extraordinary business relationships that influence others, has sold more than 45,000 copies. He's been a featured guest on 500+ podcasts, radio and TV shows. Jason has his law degree and masters in communications from Syracuse University

Jason Treu is an executive coach. He has "in the trenches experience" helping build a billion dollar company and working with many Fortune 100 companies. He's worked alongside well-known CEOs such as Steve Jobs, Mark Hurd (at HP), Mark Cuban, and many others. Through his coaching, his clients have met industry titans such as Tim Cook, Bill Gates, Richard Branson, Peter Diamandis, Chris Anderson, and many others. He's also helped his clients create more than $1 billion dollars in wealth over the past three years and secure seats on influential boards such as TED and xPrize. His bestselling book, Social Wealth, the how-to-guide on building extraordinary business relationships that influence others, has sold more than 45,000 copies. He's been a featured guest on 500+ podcasts, radio and TV shows. Jason has his law degree and masters in communications from Syracuse University

Tamsen Webster

Tamsen Webster

Scott Baradell (@dallasinbound) is president of Idea Grove, oversees one of the fastest-growing inbound marketing agencies. Idea Grove focuses on helping technology companies reach media and buyers; and its clients range from venture-backed startups to Fortune 200 companies. Scott launched Idea Grove in 2005 along with his groundbreaking blog, Media Orchard. He has been a consistent innovator in the public relations and marketing space. Scott was among the first to understand the role of blogging in audience building. He was quick to recognize the vital importance of content quality and the power of social sharing.

Scott Baradell (@dallasinbound) is president of Idea Grove, oversees one of the fastest-growing inbound marketing agencies. Idea Grove focuses on helping technology companies reach media and buyers; and its clients range from venture-backed startups to Fortune 200 companies. Scott launched Idea Grove in 2005 along with his groundbreaking blog, Media Orchard. He has been a consistent innovator in the public relations and marketing space. Scott was among the first to understand the role of blogging in audience building. He was quick to recognize the vital importance of content quality and the power of social sharing.

Patrick MeLampy (@pmelampy) is the COO and Co-Founder of 128 Technology, one of the hottest startups in Boston (and has raised $57M to date). He’s been awarded 35 patents in telecommunications. Prior to 128 Technology, Patrick was the Vice President of Product Development at Oracle. Prior to Oracle, Mr. MeLampy was CTO and Founder of Acme Packet (NASDAQ: APKT) that was acquired by Oracle in February of 2013 for $2.1 billion dollars. He’s also on the board of directors at Ipswitch. Mr. MeLampy has an MBA from Boston University, and an Engineering Degree from University of Pittsburgh.

Patrick MeLampy (@pmelampy) is the COO and Co-Founder of 128 Technology, one of the hottest startups in Boston (and has raised $57M to date). He’s been awarded 35 patents in telecommunications. Prior to 128 Technology, Patrick was the Vice President of Product Development at Oracle. Prior to Oracle, Mr. MeLampy was CTO and Founder of Acme Packet (NASDAQ: APKT) that was acquired by Oracle in February of 2013 for $2.1 billion dollars. He’s also on the board of directors at Ipswitch. Mr. MeLampy has an MBA from Boston University, and an Engineering Degree from University of Pittsburgh.