Zac Sheffer | Making Portfolio Management Simple Again (Episode 10)

Zac Sheffer (@zsheffer) is the CEO and co-founder of Elsen, and one of Boston’s hot startup companies. Elsen is a platform-as-a-service company that enables anyone at large financial institutions to harness massive quantities of data for better decision making and problem solving. An engineer by training, Zac worked at Schneider Electric before catching the finance bug. During a later position at Credit Suisse, he applied his engineering and programming skills to macroeconomic research. His ability to create solutions that address complex problems in manageable ways gave him the tools he needs to solve difficult finance problems, and led him to Elsen. What Zac loves most about Elsen is its talented team of dedicated people who want to do something incredible every day. When he’s not leading the team, he enjoys longboarding, surfing, cooking, watching Chef’s Table, and playing board games. Zac holds a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Northeastern University and holds several patents.

Zac Sheffer (@zsheffer) is the CEO and co-founder of Elsen, and one of Boston’s hot startup companies. Elsen is a platform-as-a-service company that enables anyone at large financial institutions to harness massive quantities of data for better decision making and problem solving. An engineer by training, Zac worked at Schneider Electric before catching the finance bug. During a later position at Credit Suisse, he applied his engineering and programming skills to macroeconomic research. His ability to create solutions that address complex problems in manageable ways gave him the tools he needs to solve difficult finance problems, and led him to Elsen. What Zac loves most about Elsen is its talented team of dedicated people who want to do something incredible every day. When he’s not leading the team, he enjoys longboarding, surfing, cooking, watching Chef’s Table, and playing board games. Zac holds a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Northeastern University and holds several patents. (On Networking): “It’s definitely an incredibly important thing. I would say the first two years that we were doing Elsen, I was at every single event I could possibly go to talking to every single person I could possibly talk to. It’s a pain in the butt, but I think that’s part of the reason why we now actually are having a good reputation, a lot of people know about us and we have a pretty good network of people that we can go to. Obviously, we are continuing to do that and continuing to grow, but I think that’s one of the really important things that I would highly recommend to anyone who is actually trying to do something.” –Zac Sheffer

“Big part of building a great culture is you just have to respect the other people around you and continue making sure that everyone is pushing forward together.” –Zac Sheffer

(On a rock bottom moment): “I think one was probably about a year ago. We were, I guess kind of gesturing to get ramping up with some of the stuff with Thomson Reuters, and we unfortunately realized that some of the folks on the team weren’t who we needed on the team at that point. We were only 6/7 people and we realized that we need get rid of 4 of them.” –Zac Sheffer

“We took money too early and then we didn’t take enough, so I’ve got an interesting experience where I think you should bootstrap as much as possible and in fact if you don’t ever have to raise money then don’t raise money because it changes the dynamic of what you’re doing and if you don’t have to you shouldn’t. But then when you do start raising money raise as much as possible, because being in the experience where you don’t have enough resources to do something is not a position you want to be in.” –Zac Sheffer

“I think you kind of have to almost lie to yourself a little bit, right? I kind of hate saying that, but you need to convince yourself that, if this is actually the correct path to go down, that it’s the correct path to go down. You have to put everything, no matter what, for as long as it’s going to take in order to make it successful. Whether … unfortunately, if you have to get rid of people, if people leave, if you run out of money, you still gotta do it.” –Zac Sheffer

“I think one of the most important one is being able to simplify a message. I find that that’s actually one of the traits that I find most impressive from a lot of the CEO’s that I respect is, they’re taking one of the most complex ideas, or most complex industries and actually being able to boil it down and translate that to everyone else. Because if you can do that, then you’ll be able to bring on people onto the team, you’ll be able to get funding, you’ll be able get cli … you’ll be able to do whatever you need. That I think, is also one of the most difficult things in the world to do is, make a complex idea simple.” –Zac Sheffer

The Cheat Sheet:

- How to manage doubt, despair and other negative “d” words

- What’s are the two keys of building a great culture and how to apply them

- Learn why getting involved and applying yourself in highschool can give you a huge advantage in college and beyond

- Learn the positives and minuses of bootstrapping versus raising money

- Get key insights on the hiring process and why you need to get a detailed process

- Why pivoting your business idea/concepts is a must, and what you need to do

- Get key lessons on being on entrepreneur and leader that you can implement

- And so much more…

Scroll down more for a summary, show transcription, resources and more.

You’ll notice immediately Zac’s candor and openness in sharing his life journey, his missteps and experiences. That’s means there is a lot you can learn from and glean from listening to him. We packed A LOT into this 35 minute interview.

Here is a glimpse:

“I remember there was the most difficult conversation … I remember with Ryan Johnson, who’s the … one of the co-founders. It was at one of the very beginning … we were having a conversation just about how to split up the equity for Elsen, which is I think one of the most tense conversations I’ve every had about Elsen. You gotta turn in to it and be open about everything with your co-founders, and you need to make sure that there’s full transparency about everything, that everyone is completely on board with anything, and that you really do trust those people basically, I don’t know … I don’t want to say with your life, but close to it. We ended up sitting down for four or five hours for that conversation and it was a hard conversation. We were loud and passionate during that time, and I think you’ve gotta find those people that you trust that you can have that frank open conversation with but still know that, hey, you love them at the end of the day..”

Listen, learn, laugh, and enjoy this interview with Zac!

Show Full Transcript

Speaker 1: Welcome to another episode of Executive Breakthroughs. I have a fantastic guest here, I’m really excited and we have a beautiful view, which I think you can see part of in the picture. I’m with Zac Sheffer. He is the CEO and Co-founder of Elsen, and we are going to get in some fascinating stories of his background, how he’s built this company, and what he’s up to now. So welcome Zac.

Zac: Awesome, thanks for having me.

Speaker 1: Hey, well thanks for being here and thanks for providing us with this magnificent view in Boston. I’d just like to find a little bit about how you grew up, what happened, kind of just give me a little bit of the background of where you came from.

Zac: Yes. So, I grew up just outside of Boston and San Diego.

Speaker 1: Both.

Zac: It’s actually a beautiful day here in Boston, so not regretting why I actually moved now.

Speaker 1: Yes.

Zac: I guess the reason why I ended up moving to Boston … my older sister had moved out, so it was just me and my mom, and my mom, whenever I was supposed to pick my college, she was like, “So Zac, just as a quick heads up, I’m gonna be selling the house, so take whatever you want.” So I was like, “All right, well I better take this opportunity and go somewhere completely different.” I ended up only applying to schools in Boston and New York, fell in love with Northeastern when I was visiting and went here. I’ve been in Boston for the better part of about eight years now, spent some time in Chicago and some time in DC though.

Speaker 1: Growing up, did you have any mentors or people that really influenced you, before you got to school and made the trip cross country?

Zac: Yeah. I had a couple of teachers, professors, in high school that were pretty influential. One guy was this … one of our biology teachers, his name was Jay [inaudible 00:02:11]. Probably one of the smartest people I’ve ever met, and it was great, because I sort of knew him as a teacher, and then we ended up going to Africa together twice, ended up actually building a really good personal relationship with him, and then he unfortunately got cancer a passed away, which was-

Speaker 1: Oh wow, that’s crazy.

Zac: It was pretty sad.

Speaker 1: Pretty intense. What did he teach you, or what did you take away from that experience that really kind of changed you in how you lived your life?

Zac: I think one of the things that was so interesting about him was, he had a PhD from Stanford, could have been a professor, pretty much done whatever he wanted and he spent his time teaching high school kids how they could change the world. We ended up going to Africa doing … setting up a DNA bar-coding laboratory at the College of Wildlife Management in Mweka. We ended up winning some national awards for bushmeat.

Speaker 1: Wow.

Zac: That was the thing that he taught me was, even high school kids can actually have a real impact. I think that was something that was really, really important for me as I grew up.

Speaker 1: And it was like your entrepreneurial start?

Zac: Yeah, that was definitely a big part of it. I think I was really lucky, I went to a charter school in San Diego called High Tech High, part of the nerdy name, but it was a really … I guess, fantastic experience for me. I think looking back on my life, how lucky I actually was, getting the opportunity to go there, because I studied engineering and we built ballistas, ended up building videos that won national awards, and actually did things that have now really changed what I want to do now in my life.

Speaker 1: You started really the technical aspects of what you’re doing now, pretty young then, being in that sort of educational environment, compared to what most people do.

Zac: High Tech High was a project based learning, so I think the most important thing that I learned was, you have no idea what you’re doing on any of these things when you first look at some of these projects, but you figure it out, you break down the steps and anyone can do them. It doesn’t really matter what problem you’re trying to solve, if you think about the steps that you’re going through, you break it down, you work with people around you. You can do it, you can do some pretty amazing things.

Speaker 1: You can figure it out in your own way.

Zac: Exactly.

Speaker 1: Then you came out here to school and what happened during college out here? Your formative years at that point.

Zac: I was studying mechanical engineering, which I absolutely love. If you want to talk about heat transfer and fluid mechanics, we can do that for the next couple of hours. No? All right.

Speaker 1: My dad’s an industrial engineer, sorry was, so he did all that stuff.

Zac: I went to Northeastern University, and Northeastern has their co-op program. So, basically I took six months off, three times, almost 20 months off of school to go and work at different jobs. So my first job, I was again, actually really lucky with the placement. I was working at American Power Conversion writing heat transfer and fluid mechanic programs for data center design. My first boss was again, one of the smartest people that I’ve ever met. Super hard working, really cared about his employees, and through that position I think we ended up getting four or five patents under some of the new stuff that we had developed.

Speaker 1: Wow.

Zac: So while in school, doing things that I hadn’t even finished in school, I was able to actually do some really impactful stuff, which was really, really exciting.

Speaker 1: And you have patents?

Zac: Yes. Yes, so we ended up-

Speaker 1: That’s big!

Zac: Well we filed some patents for that, we ended up filing another patent for some other work we had done in our senior year, and then Elsen has some patents as well. So, got a couple of things at this point.

Speaker 1: You finished college, and then you continued down this path in engineering, correct?

Zac: Sort of. I love engineering. I love actually building things, and I had worked at a company doing unmanned underwater vehicles for a little while, had … actually building real things, which was really cool, but it’s really slow building stuff. Then I kind of got into software development, and I really liked how the iteration time was a lot faster, and so I kind of got into the software and then one of my friends was really into trading. We kind of started talking about the stock market, and I don’t know what it was, but I just fell in love with that. I think all the math and physics and engineering that I was doing at work and at school, just so well applies to the financial markets, once I got stuck, I fell in love.

Speaker 1: You just wanted to figure out new things and how you can apply it. How’d you figure out the current business then? Because I know you have a couple co-founders, how did you get this all in your head about how all this could work?

Zac: Well it’s kind of evolved over a couple of … what’s the start-up term? Pivot?

Speaker 1: Yes, pivots.

Zac: Pivots, lots of pivots. Because when we first got started we actually wanted to help retail investors, actually just help regular people make better investment decisions, and that’s … we were like, “Okay, let’s take technology that the most cutting edge hedge funds have, and actually deliver it to a regular person.” That was our initial thesis, but the problem with that is most individuals don’t have any money, and they don’t want to give us the money, which sucks as a business.

Speaker 1: That makes it difficult.

Zac: We were like, “Okay we got this really cool technology that we’ve been developing. We know that it’s actually ready for hedge funds, let’s give it to the hedge funds.” We started pivoting over to the institutional side, we kind of took some of the experience from … I had worked at [inaudible 00:08:04] for a little while, running financial models for them, and we’re able to figure out what we were up to.

Speaker 1: How’d you convince the hedge funds to use your stuff? I think it’s really important for people, to share how did you crack that first egg, or first nut to get them inside the door?

Zac: In all fairness, we kind of just made it up as we went along, I wish I had a better answer. I remember we had one hedge fund client that we were talking to, I was trying to sell to, for a little over six months. At the end of the day, they were like, “Okay, you guys have literally everything we want. This product is perfect, but we just need a bigger name behind it.” So, we went and started working with Thomson Reuters on a first commercial product, and that relationship took us over 18 months. The way we were able to get it was, every single day, talking to new people at Thomson Reuters, talking to … showing them new things that only we could build and over a long time of hitting our head against a wall, we got through it. We tried to bring on advisors that could help push things through, but it was just a lot of time.

Speaker 1: Helping people solve their pain in building relationships with the people at Thomson Reuters and a lot of them, is that kind of what …

Zac: Yeah. The biggest part of it was just time. At many points I think we were told from some of our investors and advisors, “Wow, you guys are spending a lot of time on this. Make sure that it’s actually gonna work out.” And kind of just have to trust your gut and make sure that it’s actually gonna go along.

Speaker 1: And the people that you’re working with in the company right now, I mean, you can trust them too and they have to trust you. It has to be really difficult in those moments where you were having to go in there and spend more time, and then you weren’t getting anything from it. Then to take the next couple steps afterwards, how … what kind of mindset, or what did you just have to do, or do you just have this belief in what you were doing, and optimism that just said, I’m just gonna keep going till it works?

Zac: I think that’s kind of part of it. I think you kind of have to almost lie to yourself a little bit, right? I kind of hate saying that, but you need to convince yourself that, if this is actually the correct path to go down, that it’s the correct path to go down. You have to put everything, no matter what, for as long as it’s going to take in order to make it successful. Whether … unfortunately, if you have to get rid of people, if people leave, if you run out of money, you still gotta do it.

Speaker 1: You still gotta go, but at least you had a co-founder at that point, you were working … at least you had that as support.

Zac: Oh, no, I don’t think I would have been able to get through it if it wasn’t for the people on our team, unless it wasn’t friends and family and advisors and investors, because at the end of the day, starting a company you’re trying to create something from nothing and you’re trying to convince the world that you’re the only person that can do this. You’re the only one who has this idea and you’re the only one who can create it, which is ultimately kind of a hard thing to figure out, so you’ve gotta convince yourself and rely on the people around you.

Speaker 1: What’s your philosophy on taking money versus boot strapping or when … talk about when you decided to take outside capital.

Zac: That’s a good one, I think … looking back on the funding … We’ve raised some money in the past. I think in some ways we didn’t take … We took money too early and then we didn’t take enough, so I’ve got an interesting experience where I think you should bootstrap as much as possible and in fact if you don’t ever have to raise money then don’t raise money because it changes the dynamic of what you’re doing and if you don’t have to you shouldn’t. But then when you do start raising money raise as much as possible, because being in the experience where you don’t have enough resources to do something is not a position you want to be in.

Speaker 1: Because then you have to go back and ask for more, and then tell people why you didn’t ask for more in the beginning.

Zac: I also think … specifically with Elsen, obviously, things circled out longer than we anticipated at certain points and no matter what your business is, it’s going to take longer. You should make sure that you have enough padding that you can actually do all those things, because once you start down that raising money side, you have to raise more, you have to keep on doing it. There’s not a stopping point. Make sure you have enough money to get through those next stages. I don’t know, I always go back and forth on whether I would raise money again, or would I raise a lot more.

Speaker 1: It’s probably going to have to be specific to the situation you’re in and what’s driving what at that point and the people around.

Zac: I think part of the rationale as to why we wanted to raise money for Elsen is we just wanted to grow the company faster. I think we could have continued down the bootstrapping route, but we wanted to actually build [inaudible 00:13:01] company [inaudible 00:13:02] company you need to put fuel in the fire at some point.

Speaker 1: Right and if you have the recipe to do it then getting … that’s when you need money, that’s when you raise money. How do you pick the people that you were going to work with as far as advisors and investors? What did you … what kind of process did you go through to find the people that were ultimately … you chose and thought would be best suited for you?

Zac: I think for me and Elsen we … well at least I know for me personally I spoke to literally everyone I possibly could, and then everyone that they would refer me to, and literally just talked to everyone. Unfortunately many of those people aren’t actually going to be helpful, but you eventually figure out the ones that will, and now we have a core group of really strong investors and really good advisors that we really do trust, that we can go to on any problem that we actually have or any high point. I feel like that’s the most important thing, is you need to have people that are there not just at the hight points, but when things aren’t going well, that you can actually talk through and get that real advice from, and that’s-

Speaker 1: Can you talk about one of the low points, because I think it’s helpful for people to really get inside your head and actually be in that moment when things felt like they were going to spin out of control or off … because a lot of times, again … we talked about before the interview … it’s easy to see where you’re at now and all the things that are going on, but we have to take a picture of what all happened to really appreciate that at that point, because an entrepreneur’s mind is really long and you remember those days especially. Is there a specific low point or time when it was really bad, or really [crosstalk 00:14:44]?

Zac: Yeah … sorry I didn’t mean to say yeah so quickly, but anyway, I’m sure I can think of a couple of moments, I think one was probably about a year ago. We were, I guess kind of gesturing to get ramping up with some of the stuff with Thomson Reuters, and we unfortunately realized that some of the folks on the team weren’t who we needed on the team at that point. We were only 6/7 people and we realized that we need get rid of 4 of them.

Speaker 1: Wow.

Zac: That was … we were basically … we gotta drop over half the team and some of it was for unfortunate reasons, like they just couldn’t keep up, or sometimes they just were doing things that they shouldn’t be doing, but having to get rid of folks on the team, especially people who we’d been working with for a little over a year since basically the very beginning was really, really tough. That one was, emotionally, I think pretty darn draining on everyone on the team.

Speaker 1: And then have to go back to start from square one and to hire all brand new people again. What did you learn through that process, about yourself, about hiring other people, about growing talent? What were some of the things that you-

Zac: I think the thing that I learned about myself is, I don’t like firing people. It’s not very fun thing.

Speaker 1: Confrontation is hard.

Zac: I don’t mind the confrontation part, I just feel like every employee that … one of the things that I learned from one of my first bosses was, he would always spend over half of his time just dealing with employees. Being available if they need to talk about stuff, working on their existing projects. I feel like he didn’t do a whole lot of work himself, but he made sure that everyone else on the team was that much more productive, and he had a vested interest in making sure that everyone was. I try to do that same thing, so all the people that we let go and everyone on the team, I really do care about them. Whether I personally like them or not, I still want them to be successful. Emotionally it was so draining getting rid of someone that I just don’t want to ever do that again, so now we’re really, really careful about who we hire and bring onto the team and do that really, really slowly, make sure that we are actually willing to spend the next 10 years of our life with that person.

Speaker 1: What are you doing differently now, specifically, are you asking different questions, are you doing different things with them, or what is it that’s changed?

Zac: I think there was … I think one part of it was we ended up bringing on some of those folks at a time before we actually needed them, we were like, “We’re probably going to need these people soon, let’s bring them on and get them up and ready to go,” and then as things pivoted, as things changed, that didn’t happen and then they were in a role that they weren’t fit for. Then I think the second part, in coming back to being an entrepreneur is you kind of have to trust your gut on some of these things and someone may look great on paper and might sort of provide the right answers but if you don’t have that … if you don’t have that feeling that it’s going to work out then you should trust that. Especially at a very early stage company where you’re in the trenches with them for a long period of time.

Speaker 1: Yes.

Zac: You’re going to be relying on these people a lot more hours than what’s written their offer letter, and everyone knows it, so make sure that you really want them to be that person that you’re willing to rely on.

Speaker 1: Spend a lot of time with [inaudible 00:18:31] business.

Zac: You spend more time with them than your significant other in many cases, which is kind of depressing, but [inaudible 00:18:38].

Speaker 1: It’s kind of like family then, in the early part of the business.

Zac: It absolutely is, which is definitely an interesting thing.

Speaker 1: Talk about co-founder communication and conflict resolution, because I think a lot of people who start businesses who are working with it, no matter what scale it is, that’s a challenging piece of it. How do you work through things? How do you communicate with people, collaborate, stay in sync over time? What’s your thoughts and what do you do, and what have you learned on [inaudible 00:19:13]?

Zac: I remember there was the most difficult conversation … I remember with Ryan Johnson, who’s the … one of the co-founders. It was at one of the very beginning … we were having a conversation just about how to split up the equity for Elsen, which is I think one of the most tense conversations I’ve every had about Elsen. You gotta turn in to it and be open about everything with your co-founders, and you need to make sure that there’s full transparency about everything, that everyone is completely on board with anything, and that you really do trust those people basically, I don’t know … I don’t want to say with your life, but …

Speaker 1: It’s close to it, essentially because you’re putting everything and your energy into this business. It’s all … it’s really all of you.

Zac: We ended up sitting down for four or five hours for that conversation and it was a hard conversation. We were loud and passionate during that time, and I think you’ve gotta find those people that you trust that you can have that frank open conversation with but still know that, hey, you love them at the end of the day.

Speaker 1: You’re okay after the end of five hours. It’s not like the relationship is in jeopardy teetering on the edge of …

Zac: Exactly, right, and it’s really hard I guess, building up that trust, building up that relationship, and it took a lot of time for us to get to where we could basically be yelling at each other, and then be completely okay with it five minutes later. That’s kind of where we’re at now, which is really important, I know that at any point I can go and talk to them and be … tell them about anything, and whether it be personal or work related, and everything will be fine.

Speaker 1: Talk about culture building and how you view that inside and building a start-up company, and how you view that now, right as you’re building this company bigger and bigger and then it’s actually stretching out externally to other people that you’re working with and clients and …

Zac: Coming back to part of the reason why we had to get rid of a couple of people is … part of it was because of the cultural fit. I think a big thing that we look at is, everyone works really, really hard. Everyone is a high performer, but that you still trust the people around you, right?

Speaker 1: Yes.

Zac: It’s high performance, just do what you need to do to be successful, those are I think a lot of the things we kind of look at when we look for people to add to the team.

Speaker 1: People that have skin in the game.

Zac: Definitely the skin in the game. I don’t know, I find a big part of it is … and we have really difficult conversations all the time, just because we have a lot of conflicting opinions about major decisions that we’re making every day, and you have to trust the other people … We’ve got a lot of people on our team that are all really good at everything that they do, and so whenever they make a decision they’re usually … they tend to be correct and so we’ve got other people that are also making conflicting decisions, and it’s making sure that you trust and respect the other people around you. That you’ve set clear guidelines around who is actually responsible for making decisions, who is helping inform decisions, but that … I think that kind of helps clarify things, but a big part of it is, you just have to respect the other people around you and continue making sure that everyone is pushing forward together.

Speaker 1: How do you coach the people in your business? As a leader of the business, how do you help them grow and get to the next step in what they need to do? Even in a start-up company too, it’s important to have, obviously, these conversations with them, to help them, because that helps the business obviously.

Zac: One thing that we like to do is … we have quarterly reviews for everyone, so we like to understand both how people should … on a very quantitative stand point, where the company wants people to improve, but also where they want to improve, and then as much as possible trying to push people into those different things. Whether it’s getting them involved in other types of meetings that they normally wouldn’t do, getting them to present in front of other people, getting them to actually take more responsibility in certain things. I think it’s just not being afraid to push people into those things, and I think … it’s kind of weird because I’m actually I think one of the youngest people on our team, not being afraid to push people into those things, and have those difficult conversations when someone isn’t doing what they need to do and you need to pull them in. You just gotta overcome that and do it.

Speaker 1: How do you surround yourself with people that will help you see your own blind spots and that will help you grow? Because a lot of times, people … that’s a tough thing for some people that are leading a company and some people navigate that well, some people don’t, how do you look at that and …

Zac: That’s a good question. I think I like to think that I know where my weak spots are, I don’t know, sometimes I think that I purposely don’t like to [inaudible 00:24:37] just out of being a pain in the butt sometimes. I think it comes back to talking to as many people as possible. Talking to everyone who you could possibly talk to and everyone who they’ll introduce you to and finding those people that you, again, trust, that you respect and then looping them in as much as possible.

That’s a big part of how we’ve been able to bring on two of the folks on our executive team is … One of them was a referral from one of our investors who we had known for about 18 months. One of them was actually an advisor for one of our investors, who I had known for about 18 months. It was through kind of luck of knowing these other people and talking to them for a long period of time and actually trusting and respecting them. I know that they have a ton of experience, a ton of expertise that I’ll, just because of my age, won’t be able to have and I hope that they’re giving me the good advice for that.

Speaker 1: It’s also the relationship building, because I think one of the things that you mentioned early on, which a lot of people do not do is get out there, meet people, build these relationships and then continually to do it over the life span. Because usually what I see is that, people will do it and then it drops way off, and then all of a sudden they don’t have anything, and then you re-start it and it’s really, really hard.

Zac: You can’t do that.

Speaker 1: You can’t do that. How do you-

Zac: You just keep going to them, and in all fairness I’m not a big fan of networking events.

Speaker 1: We know more now, I think networking in terms of relationship building is just meeting people in various formats, like going out and setting up dinners things with people, or going in smaller environments that are more conducive so you can actually just meet more people.

Zac: Well there … I mean I just I … I also just like talking to people. I just find it interesting talking to new people and smart people that have new ideas. One of the things that I like to do is, we contribute to a couple of different meeting groups, meetup groups, like TechSandBox, which is a thing that we’ve been part of for a number of years here in Boston.

Speaker 1: And you spoke there, so [crosstalk 00:26:43].

Zac: Oh, cool, so we continued to work with that group. We have presented at other things, we’ve organized events for them, so that’s an easy way that we’re always keeping up what are other cold start-ups doing. Who are the other interesting people in the community, other sponsors and stuff and that’s a really easy one that helps me do that. The other easy way, is rely on … I guess now that we’ve got a pretty good core team, they’re always going to things and just making sure that you’re talking to those folks. Again, now that we’ve got this really strong core group of employees and advisors and investors, always just going back to them, like hey, “Who’s that new person that you should talk to?” You’ve just gotta always be willing to do five of those meetings a day, and talk to people.

Speaker 1: And now, as the company’s gotten more cachet it’s … this community here in Boston has [inaudible 00:27:39] is very small and it’s easier to meet people. You have to take the time out, and that’s what a lot of people don’t do, is just continually take the effort and the time out of their schedule because they rationalize, I have to do something else, but at the end of the day, like what you said, you found multiple people in your business through other people. If you didn’t do that they wouldn’t be there in the business and the business would be significantly weaker because of it-

Zac: Exactly.

Speaker 1: Then where it is right now.

Zac: It’s definitely an incredibly important thing. I would say the first two years that we were doing Elsen, I was at every single event I could possibly go to talking to every single person I could possibly talk to. It’s a pain in the butt, but I think that’s part of the reason why we now actually are having a good reputation, a lot of people know about us and we have a pretty good network of people that we can go to. Obviously we are continuing to do that and continuing to grow, but I think that’s one of the really important things that I would highly recommend to anyone who is actually trying to do something.

Speaker 1: … is to get out there and network and also it’s doing things other people don’t want to do, right, you said you’re going to all these meetings, doing all these things, well a lot of people … most people wouldn’t … 99% of people wouldn’t do what you did, but that’s why you are where you are.

Zac: Something like that, the other thing I would say is also just make sure you’re actually talking to people at those things and … I know a lot people go to events and then don’t really actually talk to new people. Always make sure you’re building those relationships with those people. Some of the people that I’ve met, at some of the first things, two or three years ago, I’m actually now really good friends with and I know that those people will be friends that I’ll have for a long period of time or be really helpful to Elsen.

Speaker 1: Did you follow up with them at the event and suggest doing something outside of it, meeting up, doing something? How did you kind of take that initial meeting with them for the first time into something more than it is then?

Zac: I think probably for the first couple of years, I was drinking 8 or 10 cups of coffee a day.

Speaker 1: Oh, wow, that’s a lot of coffee.

Zac: It was a dangerous amount, but that’s what I did, was just drink coffee with everyone, just go and get a cup of coffee, and again, I feel like you … part of it is all of those people, they have a different way of looking at a problem and maybe they have a different perspective or some random person who they know that’s actually running the company that you want to talk to and you just have to be able to go and talk to those people. I always really enjoyed those things.

Speaker 1: What leadership qualities and traits do you think are most important for a CEO to have, and things that you may have seen in other people that you think are exemplary, and other things you think are things that are really challenging for a business if someone has those types of qualities or traits?

Zac: I think one of the most important one is being able to simplify a message. I find that that’s actually one of the traits that I find most impressive from a lot of the CEO’s that I respect is, they’re taking one of the most complex ideas, or most complex industries and actually being able to boil it down and translate that to everyone else. Because if you can do that, then you’ll be able to bring on people onto the team, you’ll be able to get funding, you’ll be able get cli … you’ll be able to do whatever you need. That I think, is also one of the most difficult things in the world to do is, make a complex idea simple.

Speaker 1: You really have to understand the idea and are passionate about it and driving on the bleeding edge in order to simplify it backwards and probably lead them in a vision that’s going to get people [inaudible 00:31:23].

Zac: You just have to practice so bloody much. That’s the hard part, is that you just have to also do it so many times to actually have that message be succinct to get other people to trust you behind it, because I guess if you’re the CEO, you’re trying to now convince other people that, hey, this is something that they should be putting years of their life behind. That somehow this idea, this message is the thing that will actually lead them to success. That’s I think definitely the most impressive one that I’ve found.

Speaker 1: What’s next for you in this business now? Where do you all want to go? Where’s next for you is … you think as a CEO on your progression path I’m interested in seeing kind of like what the future looks like.

Zac: Right now, Eslen is focused on two big things. One … sorry … getting over that cold.

Speaker 1: Nice.

Zac: Sorry about that. One part is we’re taking the underlying platform that we developed for basically over the past four years and starting to add on more partners, more data sets and get that platform better distributed globally. The second is we’ve got this first commercial application with Thomson Reuters, which is actually being distributed globally now. We need to ensure that that’s actually successful. Those are our two big priorities over the next 12 to 18 months. I think for me personally, I’m really focused on continuing to expand the team. I’d like to bring on some more resources so that way we can continue to actually achieve all those things.

I think the thing that I want to get better on is actually making sure that our message is being distributed to a larger group of people. It’s kind of easy when you’ve only got 6, 10 people, but as we actually grow to 10, 20, 30, 40 people making sure that the organization as a whole is continuing to have that culture that we want, is continuing to actually be quantitative, is continuing to be successful. I don’t really know … that’s what I need to figure out how to do.

Speaker 1: How do you manage your personal life and people on a team and have it stay afloat as you’re managing to do all the stuff inside the business, and prioritize it in a way? Have you figured out how to …

Zac: I have not figured it out no. Sorry, that was it. I’m definitely still trying to figure out the work/life balance thing.

Speaker 1: I don’t really think there’ll be balance, it’s just how do you keep them both in a good place and …

Zac: I think a big part of it is … and the part of the nice thing about being the CEO, is that you can bring people on that do the stuff that you don’t really want to do anymore. I do a lot of stuff that I … I love Elsen, it’s my favorite thing in the world, so i never really feel like a lot of the stuff that I’m doing actually is work and I always really enjoy it, which I think is really helpful. That’s I think a big part of it, continuing to bring on more people that I think can help us grow that vision, grow that company. Does that answer your question?

Speaker 1: Yeah.

Zac: Okay.

Speaker 1: No, that’s fantastic. Well, I would like to thank you for spending some time with us today on another episode of Executive Breakthroughs, and Zac’s given us a lot of great information in taking along his trajectory in life with the business so far and be really excited to see how everything moves forward and continues to take off, like a hockey stick up, right?

Zac: Exactly, exactly.

Speaker 1: Thanks all for tuning in and we will talk to you on the next episode.

Zac: Awesome, thank you.

Speaker 1: Thanks, I appreciate it. It was awesome. Loved it, it was a lot great stuff in here, so that’s fantastic to share with people and insights and stuff so it was great.

Quotables:

“My first boss was again, one of the smartest people that I’ve ever met. Super hard working, really cared about his employees, and through that position I think we ended up getting four or five patents under some of the new stuff that we had developed.”

“I had worked at a company doing unmanned underwater vehicles for a little while.”

(On the evolution of his business): “Pivots, lots of pivots. Because when we first got started we actually wanted to help retail investors, actually just help regular people make better investment decisions, and that’s … we were like, “Okay, let’s take technology that the most cutting edge hedge funds have, and actually deliver it to a regular person.” That was our initial thesis, but the problem with that is most individuals don’t have any money, and they don’t want to give us the money, which sucks as a business.”

“In all fairness, we kind of just made it up as we went along.”

“I don’t think I would have been able to get through it if it wasn’t for the people on our team, unless it wasn’t friends and family and advisors and investors, because at the end of the day, starting a company you’re trying to create something from nothing and you’re trying to convince the world that you’re the only person that can do this. You’re the only one who has this idea and you’re the only one who can create it, which is ultimately kind of a hard thing to figure out, so you’ve gotta convince yourself and rely on the people around you.”

“Emotionally it was so draining getting rid of someone that I just don’t want to ever do that again, so now we’re really, really careful about who we hire and bring onto the team and do that really, really slowly, make sure that we are actually willing to spend the next 10 years of our life with that person.”

“That was the thing that he taught me was, even high school kids can actually have a real impact. I think that was something that was really, really important for me as I grew up.”

(On hiring mistakes): “I think one part of it was we ended up bringing on some of those folks at a time before we actually needed them, we were like, “We’re probably going to need these people soon, let’s bring them on and get them up and ready to go,” and then as things pivoted, as things changed, that didn’t happen and then they were in a role that they weren’t fit for. Then I think the second part, in coming back to being an entrepreneur is you kind of have to trust your gut on some of these things and someone may look great on paper and might sort of provide the right answers but if you don’t have that … if you don’t have that feeling that it’s going to work out then you should trust that. Especially at a very early stage company where you’re in the trenches with them for a long period of time.”

THANKS, ZAC SHEFFER!

If you enjoyed this session with Zac Sheffer, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending her a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Zac Sheffer at Twitter!

Click here to let Jason know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

References Mentioned:

- His LinkedIn bio

- Elsen – Is the Platform-as-a-Service company for large financial institutions. The Elsen nPlatform enables anyone to effortlessly harness vast quantities of data to make better decisions and quickly solve the most complex problems.

- One their marque client’s, Thomson Reuters

- Article on company being one of Boston’s hot startups

- Recent press release: Elsen Unveils Platform-as-a-Service for Large Financial Institutions to Harness Big Data and Quickly Solve Complex Problems

- Schneider Electric

- High Tech High (his high school he went to)

Biography:

Zac keeps Elsen running. From recruiting and managing a top-performing executive team, to driving critical decisions and developing partnerships with world-class companies, he ensures all areas of the business are aligned with the company’s strategic goals.

An engineer by training, Zac worked at Schneider Electric before catching the finance bug. During a later position at Credit Suisse, he applied his engineering and programming skills to macroeconomic research. His ability to create solutions that address complex problems in manageable ways gave him the tools he needs to solve difficult finance problems.

What Zac loves most about Elsen is its talented team of dedicated people who want to do something awesome every day. When he’s not leading the team, he enjoys longboarding, surfing, cooking, watching Chef’s Table, and playing board games.

Zac holds a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Northeastern University and holds several patents for cool stuff like fluid mechanics.

Elsen Company Story:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J-WH3zZR34w

Elsen was founded by three graduates of Northeastern University who came together to tackle some of the most difficult data problems in the financial industry.

After his stint with Credit Suisse, Elsen founder Zac Sheffer realized that the tools he was using to analyze data at one of the most venerable investment banks were less sophisticated than the ones he used at school. He knew he could have a big impact on the industry if he could improve the way financial institutions used their data.

After becoming aware of what his roommate Justin White was working on at IBM and the U.S. Government, Zac realized that he had found the perfect partner to start Elsen. One day over lunch, they agreed to start working together.

Way back in 2012, Zac and Justin recognized the difference between cool technology and something that changes people’s lives. They understood that the human element – the usability – of any solution was critical to success. That’s when they enlisted their fellow Northeastern alumnus Ryan Johnson, an experienced UI/UX designer, to complete the founding team.

With its team’s diverse skills, Elsen is able to provide future-forward data science technology that’s focused on the human element and ease-of-use. Creating turnkey financial data solutions that are easily grasped by all users, Elsen is – and will continue to be – a driver of innovation in a space afflicted by deep stagnation.

On your phone? Click here to write us an iTunes review and help us reach and help more people!

Jason Treu is an executive coach. He has "in the trenches experience" helping build a billion dollar company and working with many Fortune 100 companies. He's worked alongside well-known CEOs such as Steve Jobs, Mark Hurd (at HP), Mark Cuban, and many others. Through his coaching, his clients have met industry titans such as Tim Cook, Bill Gates, Richard Branson, Peter Diamandis, Chris Anderson, and many others. He's also helped his clients create more than $1 billion dollars in wealth over the past three years and secure seats on influential boards such as TED and xPrize. His bestselling book, Social Wealth, the how-to-guide on building extraordinary business relationships that influence others, has sold more than 45,000 copies. He's been a featured guest on 500+ podcasts, radio and TV shows. Jason has his law degree and masters in communications from Syracuse University

Jason Treu is an executive coach. He has "in the trenches experience" helping build a billion dollar company and working with many Fortune 100 companies. He's worked alongside well-known CEOs such as Steve Jobs, Mark Hurd (at HP), Mark Cuban, and many others. Through his coaching, his clients have met industry titans such as Tim Cook, Bill Gates, Richard Branson, Peter Diamandis, Chris Anderson, and many others. He's also helped his clients create more than $1 billion dollars in wealth over the past three years and secure seats on influential boards such as TED and xPrize. His bestselling book, Social Wealth, the how-to-guide on building extraordinary business relationships that influence others, has sold more than 45,000 copies. He's been a featured guest on 500+ podcasts, radio and TV shows. Jason has his law degree and masters in communications from Syracuse University

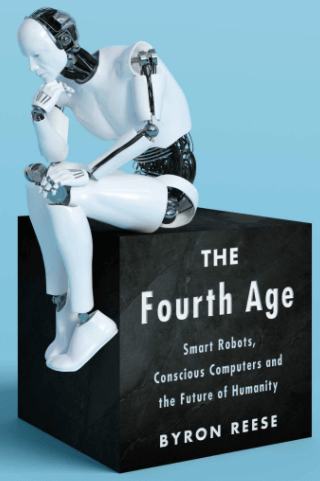

Byron Reese (@byronreese) is an investor, entrepreneur, publisher and futurist. He is the publisher of tech news site Gigaom and the founder of several high-tech companies. He has obtained or has pending patents in disciplines as varied as crowdsourcing, content creation, and psychographics. He is the author of the best selling book, Infinite Progress: How Technology and the Internet Will End Ignorance, Disease, Hunger, Poverty, and War. He currently serves as Chief Executive Officer for Knowingly, a venture-backed Internet startup based in Austin, Texas.He also has a TEDxAustin talk on “Achieving Greatness is a Choice.”

Byron Reese (@byronreese) is an investor, entrepreneur, publisher and futurist. He is the publisher of tech news site Gigaom and the founder of several high-tech companies. He has obtained or has pending patents in disciplines as varied as crowdsourcing, content creation, and psychographics. He is the author of the best selling book, Infinite Progress: How Technology and the Internet Will End Ignorance, Disease, Hunger, Poverty, and War. He currently serves as Chief Executive Officer for Knowingly, a venture-backed Internet startup based in Austin, Texas.He also has a TEDxAustin talk on “Achieving Greatness is a Choice.” The Fourth Age is his upcoming book. Byron Reese explains that a number of disruptive technologies—each of which alone would be world-changing—are all converging at the same time in a perfect storm. We are building robots that can do human jobs. We are designing computers that might be capable of intelligence. We are likely on the cusp of creating a new life form: a conscious computer to which we could outsource our thinking minds, with a companion robot to perform the functions of our bodies.

The Fourth Age is his upcoming book. Byron Reese explains that a number of disruptive technologies—each of which alone would be world-changing—are all converging at the same time in a perfect storm. We are building robots that can do human jobs. We are designing computers that might be capable of intelligence. We are likely on the cusp of creating a new life form: a conscious computer to which we could outsource our thinking minds, with a companion robot to perform the functions of our bodies.

Tamsen Webster

Tamsen Webster

Scott Baradell (@dallasinbound) is president of Idea Grove, oversees one of the fastest-growing inbound marketing agencies. Idea Grove focuses on helping technology companies reach media and buyers; and its clients range from venture-backed startups to Fortune 200 companies. Scott launched Idea Grove in 2005 along with his groundbreaking blog, Media Orchard. He has been a consistent innovator in the public relations and marketing space. Scott was among the first to understand the role of blogging in audience building. He was quick to recognize the vital importance of content quality and the power of social sharing.

Scott Baradell (@dallasinbound) is president of Idea Grove, oversees one of the fastest-growing inbound marketing agencies. Idea Grove focuses on helping technology companies reach media and buyers; and its clients range from venture-backed startups to Fortune 200 companies. Scott launched Idea Grove in 2005 along with his groundbreaking blog, Media Orchard. He has been a consistent innovator in the public relations and marketing space. Scott was among the first to understand the role of blogging in audience building. He was quick to recognize the vital importance of content quality and the power of social sharing.

Patrick MeLampy (@pmelampy) is the COO and Co-Founder of 128 Technology, one of the hottest startups in Boston (and has raised $57M to date). He’s been awarded 35 patents in telecommunications. Prior to 128 Technology, Patrick was the Vice President of Product Development at Oracle. Prior to Oracle, Mr. MeLampy was CTO and Founder of Acme Packet (NASDAQ: APKT) that was acquired by Oracle in February of 2013 for $2.1 billion dollars. He’s also on the board of directors at Ipswitch. Mr. MeLampy has an MBA from Boston University, and an Engineering Degree from University of Pittsburgh.

Patrick MeLampy (@pmelampy) is the COO and Co-Founder of 128 Technology, one of the hottest startups in Boston (and has raised $57M to date). He’s been awarded 35 patents in telecommunications. Prior to 128 Technology, Patrick was the Vice President of Product Development at Oracle. Prior to Oracle, Mr. MeLampy was CTO and Founder of Acme Packet (NASDAQ: APKT) that was acquired by Oracle in February of 2013 for $2.1 billion dollars. He’s also on the board of directors at Ipswitch. Mr. MeLampy has an MBA from Boston University, and an Engineering Degree from University of Pittsburgh.

Becky Powell-Schwartz is the founder and CEO of The Powell Group, Becky Powell-Schwartz has been a thought partner to the C-suite for more than 25 years. Her depth of experience solving business and communications issues has made her a trusted advisor for executives of Fortune 500 and industry-leading companies across diverse business sectors. She is also Vistage International CEO group leader. Becky is a graduate of the Harvard University Mediation Training program, Leadership America, Leadership Texas and Leadership Dallas. She is also the recipient of the Most Powerful Women in PR Award from the Council of Public Relations. Additionally, she currently serves on the advisory boards of the Texas A&M Mays Business School Center for Retailing Studies; Leadership Women, the oldest women’s leadership program in North America; and Senior Source of Greater Dallas.

Becky Powell-Schwartz is the founder and CEO of The Powell Group, Becky Powell-Schwartz has been a thought partner to the C-suite for more than 25 years. Her depth of experience solving business and communications issues has made her a trusted advisor for executives of Fortune 500 and industry-leading companies across diverse business sectors. She is also Vistage International CEO group leader. Becky is a graduate of the Harvard University Mediation Training program, Leadership America, Leadership Texas and Leadership Dallas. She is also the recipient of the Most Powerful Women in PR Award from the Council of Public Relations. Additionally, she currently serves on the advisory boards of the Texas A&M Mays Business School Center for Retailing Studies; Leadership Women, the oldest women’s leadership program in North America; and Senior Source of Greater Dallas.